‘We need English as subject’

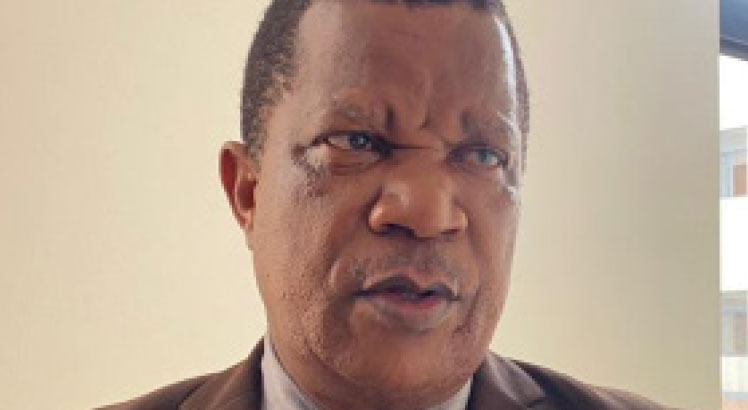

This week, the Ministry of Education announced that starting September this year pupils from standard one will be taught in English. I caught up with BENEDICTO KONDOWE of Civil Society Education Coalition (Csec) who shares his views on this directive by government.

Q. What could have necessitated government’s directive to introduce teaching in English from standard one?

A. I believe that this decision has been necessitated by the prescription in law as the new Education Act provides for English as a language of instruction. Section 78 (1) states that language of instruction in schools and colleges shall be English. But subsection (2) gives the minister discretion to determine the language for schools other than English. The subsection reads as follows: Without prejudice to the generality of Subsection (2) the minister may, by notice published in the gazette prescribe the language instruction in schools. Based on this provision, it means that unlike in colleges, English is not mandatory in schools.

Q. Why do you think this directive is coming now?

A. There could be two main factors in my view. First, government’s intention to align the matter to what is provided at law with respect to the new Education Act. Second, it could be the generalisation that our children are doing badly in English across the board.

Q. Won’t this be chaotic considering that most kids don’t even know one English word when they come to school for the first time?

A. Chaos, yes, because this is a major shift which has to be managed well. The issue should not be about a child not knowing an English word at the earliest stage, but rather whether such a decision would improve learning and learner outcomes. My own view is that we need English as a subject right from standard one so that it is taught alongside Chichewa as language of instruction from standard one to four. Unfortunately, our teachers are not well trained to the effect that they abandon English and just focus on Chichewa.

Q. But educationists the world over agree that learners learn more quickly and effectively in their mother tongue than in a second language. As an educationist yourself, don’t you think this is contradictory?

A. There is adequate empirical evidence that learners learn better in their mother tongue especially in early grades. Indeed, all the industrialised nations of Europe, the Americas and Asia use their own languages as tools for learning in schools and children learn foreign languages either as subjects or through other means. This does not suggest that English is not important in the modern world as a tool for business communication all over.

Q. What are the successes of such an arrangement in those countries?

A. It is generally held that learning in mother tongue facilitates better learning, and the Unesco report (1953) attest to this. This seems to be the trend in these days. Actually, there is growing advocacy even in countries that are doing better in English such as South Africa, Zimbabwe and Zambia for use of the child’s own language as a language of learning in the early years of primary school. This preposition is not to negate English but rather to make it as a subject rather than being a language of instruction. It must be stressed here that what matters is how teaching is designed. You may not facilitate better learning even in mother tongue if teaching is of poor quality. Similarly, English as a language of instruction is not enough in itself to improve learner outcomes if the needed ingredients for better learning and comprehension are not available.

Q. Surely teachers will need new training. How ready is Malawi considering the current problems rocking the education sector?

A. I have stated before that such a shift needs great planning and consultations with all relevant stakeholders including Teachers Union of Malawi as the ramifications for such a directive, if not done consultatively, may be grave. The call for more and well training of teacher is obvious. The directive is an overhaul, at least for early grades (1-4) that currently use Chichewa as language of instruction.

Q. What kind of resources would be required for the smooth running of the arrangement?

A. Government will need to train more teachers in the subject matter as a subject. Those already in the system will need to be exposed to refresher training maybe when schools are on holidays to make up for the gaps in skills. Schools will need to be provided with a variety of teaching and learning material in the subject matter to aid learning. Above all, there will be need to create incentives among learners themselves. This is why there is need for the involvement of all major players to avoid resentment which may negatively cost the directive.

Q. What should be done to accommodate parents and guardians in this arrangement?

A. Parents and guardians are indeed major players, and they need to be taken on board. Already the new Education Act envisages a greater role played by these stakeholders as primary education is expected to be devolved to local assemblies in as far as management is concerned. In fact, the first contact point in one’s education is through parents and guardians hence the buy in from these actors is crucial.

Q. Should introduction of English overhaul Chichewa as a language of instruction for these early grades?

A. I think government might consider introducing English as a subject to complement the other used language. Above all, there will be need for more national reflection on the subject matter to build consensus by the majority as the issue of use of mother tongue versus English remain debatable. Equally important is the view that teaching in mother tongue or English may not facilitate learning if they are poorly conducted: you need proper incentives for positive results.