‘Budget has responded to zero-deficit budget’

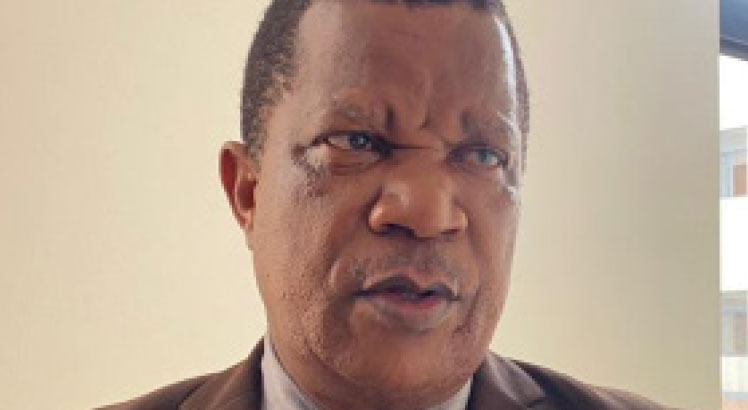

In this interview, Albert Sharra speaks with Professor Ben Kaluwa on the 2012/2013 national budget presented in Parliament last week.

How would you describe the proposed 2012/2013 national budget?

The national budget is a short-term framework and cannot be panacea to all of Malawi’s many economic problems and, especially when more have been added during the past four years. During that time, economic policies were hijacked by increasingly heavy-handed anti-market State interventions in the markets for a number of key strategic goods starting from maize and including tobacco, cotton, energy (petroleum products and electricity) and utilities such as water.

The present budget has responded to some of the unrealistic assumptions of the 2011/12 zero-deficit budget which required punitive, unrealistic and anti-business tax and non-tax revenue measures as well as normal external donor aid flows whose resources would help the external debt stock.      Â

Some commentators have described it as a difficult budget for ordinary Malawians? What is your take on this?

The proportion of Malawians living on less than US$1 a day is large, at nearly 40 percent. These would not be able to meet their daily basic necessities, including food, health services, education and shelter. There can be no budgets that can completely or meaningfully cushion all of these from shocks such as a large devaluation, especially considering that the tax base is small and the low-income are non-contributors.

Blanket cushions such as cash transfers face enormous problems, including the possibility of over-taxing the economy into a non-competitive business environment which has long-term growth, employment and poverty consequences. Budgets including this one typically intervene the food, health, education and rural infrastructure areas. Farm input subsidies target food security. Budget support at the primary health and primary education levels and rural infrastructure benefit the low-income rather than the non-poor.

Observers have argued  that the budget has been dictated to Malawi by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and it is not signalling much for the poor. What is your comment on this?

The IMF and other multilateral organisations recruit economists from the same universities that produce local economists retained in their home countries and who are required to be as critical in their thinking and recommendations as any other, especially given the context of application. Those who have been attentive to presentations by local economists over the past years would know that what this budget has done is what was being recommended for a long time.

Budgets are exactly what the term should reflect, which is aligning the achievable revenue base to what can be sustained in terms of expenditure in twelve months but laying a foundation for the future. A punitive tax regime restrains business and the tax base and yields on a long-term basis. The budget needs to be complemented by other macroeconomic policies. Some of the policies that the IMF would espouse could traverse the austerity (government expenditure and credit limiting) versus expansion debate that is dogging the US (expansion) versus European (austerity) debate.

I am a co-author of a report which devised and widely canvassed monetary policies for developing economies like Malawi’s that do not target inflation rates that are as low as 3 percent or less by severely constraining credit access when the economy needs it for job-reach growth. The financial sector can be incentivised to reduce excess-liquidity and channel the resources into output and job generating activities.

These can diversify the economy and exports out of agriculture and promote the small and medium enterprise sector (SMEs). The IMF has not been averse to such ideas and neither have other stakeholders including the Reserve Bank of Malawi, which was on the verge of mobilisÂing the issue namely through the proposed Development Bank.

Records indicate that government has not addressed some of the demands made by civil society organisations, for example the proposed 46 percent salary hike for civil servants and many others. What conclusions can you draw from this?

The unfortunate is in that the devaluation should not have been necessary. The salary hike has been overdue and now has been overtaken by the devaluation which is supposed to be a shock and punishment for over-intervening the foreign exchange rate.

This intervention translates into subsidies for segments of the economy which do not need them like motor vehicle importers and drivers who also need imported fuel. Others would import consumer goods which local producers would not be able to compete against. In economics an exact match for a devaluation by everyone i.e. prices and incomes going up at the same pace takes things to square one and defeats the whole purpose of the devaluation.

The budget is replacing the zero-deficit budget but allocations to most ministries have not improved much. Do you see any hope for recovery with this budget?

I see a budget of hope in terms of recovery than the foregoing one which was severely restraining to private-sector activity and Malawi’s international competitiveness in the short-medium and long-term in terms of diversifying the economy out agricultural activity and exports.