Cartoons’ humorous tales

A cartoonist’s pencil is the simplest of tools that creates illustrations on an austere landscape of paper to mirror not only the artist’s mind and his world-view, but also tell a story with impeccable subtlety and humour.

A cartoonist’s caricature is a loaded package of message. Yet, anyone can understand the message—the literate and the illiterate. Thus, making cartoons the most effective means of communication.

Elson Kambalu, a scholar who specialised in fine art, says cartoons are a more effective means of disseminating information than words.

“Even the uneducated can grasp the message in a cartoon. This makes cartoons very powerful tools to send a message across because of the humour in them,” he says.

A cartoonist tends to see things in high definition. He can notice the minutest of details from the ordinary situation. Their ability to depict that situation in artistic form does not only appeal to aesthetics but also to intellect. Cartooning is art that wears a shroud of simplicity yet, so deep in adeptness and rich in meaning and interpretation.

To read the cartoonist’s mind is to read an open book—a panorama of the conceit, images and symbolism. It is the cartoonist’s ability to draw a metaphysical world on a tapestry of reality that strikes readers with awe.

In Malawi, it is not uncommon to see cartoons in newspapers and magazines. Notable ones are political satirical cartoons although Kambalu thinks that artists in Malawi are afraid to draw cartoons that will shake the politicians much.

On his part Ralph Mawera, one skilled cartoonist in the country whose cartoons appear in The Nation, says he draws cartoons after identifying some peculiar thing in politics to critique it satirically.

“The role of a cartoonist is exactly the role of any other artist—to entertain and critique society. Sometimes people who see things through the lenses of a cartoonist see things more clearly as the artist captures some details in the illustration that might have been overlooked in ordinary situations,” Mawera says.

Every week, Malawian artists have had their cartoons used in newspapers to entertain people, critique leaders’ mistakes or rebuke social immorality.

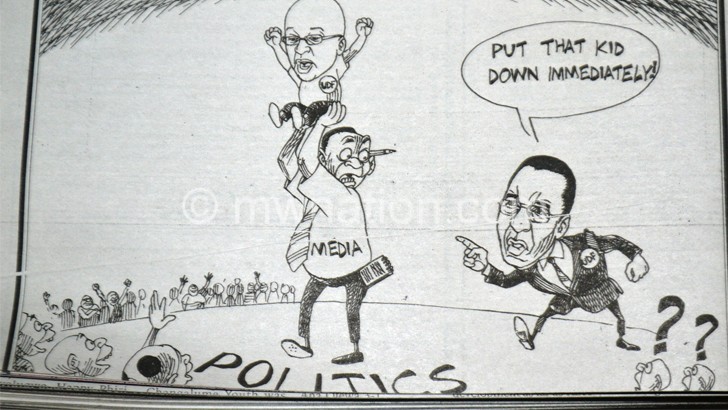

Mawera’s cartoon in The Nation of April 6 2011 is a masterpiece. In this illustration, the media is carrying United Democratic Front presidential hopeful Atupele Muluzi high up. George nga Mtafu, a notable UDF member, is not happy with this and he shouts: “put that kid down immediately.”

Atupele looks baby-like. He is clenching his fists and sits comfortably like a child on the shoulders of his father.

The media, like a caring father looks down at Mtafu with a contorted face of wonder. The body language of the media is telling. The media is a saviour and defender of this “kid” from the clutches of the Mtafu camp.

On the sidelines people are cheering—perhaps welcoming Atupele as a new leader. It is the media which is helping him rise. The media’s note-pad and pen are the weapons with which to help him. A pen is mightier than a sword, so they say.

The artist’s hidden but plain criticism is the foolhardy of intra-party political bickering which polarises leaders. This is a case of a house divided against itself. As perfectly illustrated, Mtafu’s wrath at Atupele exemplifies the entrenched political philosophy of the Leviathan animal nature.

In The Nation of March 18 2011, there is a cartoon depicting Bingu as a cruel leader holding a can, standing on a high podium, commanding the university dons to return to class. The caption: “return to class or else…” befits the portrait of an angry man bent on forcing his orders on others.

Jessie Kabwila is in front of her fellow university lecturers and she says: “we’ll not be intimidated.” The academic dons are standing in the background of a university building, the bulwark of intellect. Their books are clinging to their bodies as if their life depends on them. This is a battle for academic freedom.

While Bingu is looking intently at the lecturers, Jessie is looking away from him—communication break-down. It is a body language that speaks it all. Bingu and Jessie were always at daggers drawn.

Thus the cartoonist tells many stories in a single illustration. Looking at the world through the prism of a cartoonist, one reads many stories that volumes of books cannot suffice to contain. n