Charcoal production, consumption: The reality

There is something strange about Malawi. In school, we all think about transforming our country upon graduation. We feel convinced our ancestors and predecessors in the jobs that we are being trained to take over got things wrong and we know where to start from.

The academia conduct studies and accumulate hard evidence to inform policy formulation. It is not for nothing that we are called Africa’s policy factory and exporters. Some people even claim that most of the policies our immediate and not-so-distant neighbours implement to become rich were imported from Malawi.

In many fora, the mantra is the same: ‘Malawi is policy rich but implementation deficient’. But, very few, if any, of us question why this is the case. Well, our experience as bottom rung Malawians is that the government does not listen to researchers and policy drafters. Politicians, who are the real government don’t’ listen to outsiders, except if the outsiders were foreigners such as the loquacious conference Kenyan star, Prof Patrice Lumumba.

As one legislator is heard saying in social media, ‘government is a tough and rough machine’, that grinds its enemies and their ideas. Indeed, government is an impervious genus of Homo erectus. Due to this imperviousness, we are going in circles over the charcoal business. Sometimes we even peddle lies that charcoal production is illegal in Malawi.

In this country, charcoal production, transportation, selling, and consumption are not illegal. Those who think so should read again and again Malawi’s Forestry Policy and latest National Charcoal Strategy, 2017–2027. The Forestry Policy only forbids production of charcoal without a valid licence from the Malawi Government’s director of forestry. Basi.

If charcoal were a banned product, it would not be displayed along the streets and highways for all to buy in plain view. All politicians, in government or opposition, retired or otherwise know charcoal is not a banned product.

Banned products, such as Noah’s wisdom weed, are uprooted, or confiscated by police and the producers, usually achina kaka, ada, and badada, are quickly taken to court, charged with something like farming, trafficking and dealing in a banned product, found guilty, fined and released. No one, of course, knows where the confiscated wisdom weed ends up.

Secondly, those who have read Malawi charcoal value chain studies will have noted that charcoal is big business that involves poor rural small-scale producers who produce one to 30 bags in one month to find money for their livelihoods. These are seen every morning bicycling hard towards urban centres to sell and return home with salt, sugar and ndiwo za nkhuli for their families. Nothing more.

Sometimes, these small-scale charcoal producers get united and hire a truck to speedily transport the charcoal to town. Because they can’t bribe, kugula njira, all the way to town, their charcoal is often impounded, displayed, and sold away by the very government that pretends to abhor charcoal production, trafficking, and use of charcoal. Senior officers are often beneficiaries of the impounded product. Proof? Go to their homes.

Then there are the rural not-so-poor medium-scale category, the nkhasako, who produce up to 100 bags per month. These usually wait for people to come and buy in bulk in situ. These are well connected to customers locally and in far-away urban centres.

Finally, there are large-scale urban producers, ma bigi, who produce over 100 to 500 bags per month. This category has contracted ‘producers’ in the field. These are huge money-makers. These use large trucks to transport charcoal and pay bribes all the way.

One study indicates that members of this category include Members of Parliament, government ministers, faith leaders, business leaders, and others you already know. Their charcoal goods are rarely confiscated. Even when a truck belonging to this category is impounded by a small police officer, the truck is released at phone call directive.

A 2007 study estimated that out of the cost of a bag of charcoal that gets into the urban centre, roughly 20 percent goes into bribing the police and forestry officers; 25 percent is used to pay for transportation; 33 percent is earned by urban retailers while the producers get roughly 22 percent.

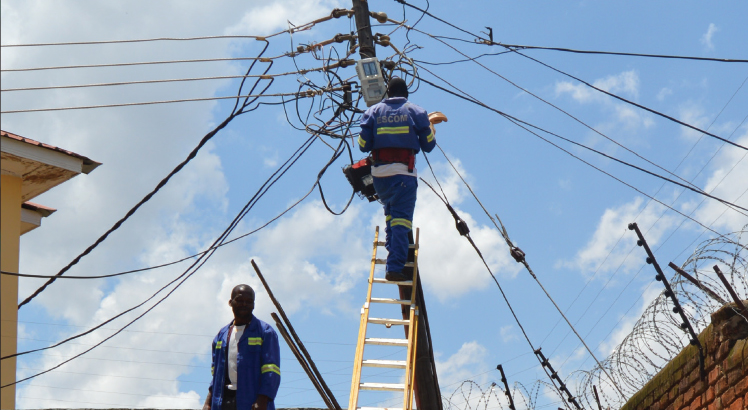

The main driver of charcoal production is urban demand for steady energy. As long as this energy demand is not met through alternative affordable energy sources, charcoal production will continue, even at gunpoint. Poor rural dwellers don’t use charcoal because they don’t need to. Poor urban dwellers use a lot of charcoal because they can’t afford the overpriced and unreliable Grid electricity.

Even if Mera reduces the price of Escom power, the charcoal business will not stop because the cookers and stoves are expensive to procure.

For the same reason, even the gas alternative being touted will not stop the charcoal business immediately; not even by 2063. Gas tanks are unaffordable to many. And storing gas can be tricky.

Cul de sac? No. Let’s think in terms of interconnected value chains that will minimise charcoal demand.