Chipembere’s rebel takeover

This week marks the 53rd anniversary of the largest armed conflict in independent Malawi, our contributor WILLIE ZINGANI writes.

Most Malawians grow up hearing their country has never experienced civil strife since independence 54 years ago.

It is misleading to suggest that after the fall of British colonial rule in 1964, Malawi never tasted the horrors of armed conflicts as experienced in many African states.

But the praises poured on post-independence leaders are not only capable of turning truths into fiction.

Sadly, they are frequently supported by statements uttered even by legislators in Parliament—the House of Records.

History has it that Henry Masauko Chipembere, a minister in founding president Dr Hastings Kamuzu Banda’s first Cabinet, on the night and early hours of February12-13 1965 led an invasion that took control of Mangochi Boma as his rebel troops targeted a coup d’etat.

Chipembere was one of the six ministers that rebelled against Banda in 1964 on internal and foreign policies.

Though the confrontation, popularly known as the Cabinet Crisis, came a long way, the hot-water splashes between Banda and ministers—Orton Chirwa (Minister of Justice), Kanyama Chiume (External Affairs), Augustine Bwanausi (Works, Development and Housing), Yatuta Chisiza (Internal Affairs) and Willie Chokani (Labour) reached a boiling point when Chipembere was at a Conference of Education Ministers in Canada which he cut short at Chiume’s request.

Chipembere arrived home to find Banda had dismissed some members of Cabinet, including junior minister of Natural Resources Rose Chibambo.

This led to resignations of others in solidarity with their colleagues as Chipembere’s attempt to effect reconciliation within 24 hours proved futile.

He too tendered a letter of resignation on September 9 1964 at 9.30am and later announced the emotional decision in the National Assembly.

The six ex-ministers then lost in a ‘vote of no confidence’ motion against Banda which the House deliberated to figure out a solution to the conflict.

However, the sacked ministers regrouped to look at options, one of which was formation of an opposition party, but Banda had already decided to teach them a political lesson he declared “they would live to remember”.

Within a month, the ex-ministers, save for Chipembere, fled into exile to Zambia and Tanzania.

Chipembere retreated to his home, Malindi where Banda quickly issued a restriction order prohibiting him from addressing meetings to explain to his constituents why he had resigned.

However, following threats on his life and clamp down on all ex-ministers’ relatives and sympathisers, he disappeared into the mountain forests in October 1964 with a few personal bodyguards who helped him recruit men for a largest ever rebel army recorded in the country’s post-independence history.

He trained 400 guerrilla fighters with the assistance of an ex-soldier Medson Envas Silombera.

On the night of February 12 1965, Chipembere led almost 200 armed fighters from Malindi and launched a military operation that took government by surprise.

His fighters forced an Anglican expatriate engineer of a mission workshop, Francis Bell, to surrender a seven-tonne lorry, Land Rover and two rifles.

They sped off to Mangochi Boma where they attacked a police station; released prisoners; destroyed telephone installations; stole maize, guns and ammunition; burned Chief Mponda’s houses; courthouse and killed wife of police Inspector Changwa.

They drove towards Zomba where they were blocked at Liwonde because a ferry was on the southern bank of Shire River.

It remains unknown where exactly Chipembere obtained arms for hundreds of rebels in a matter of months.

By the following morning, government troops still under the command of a British colonial Brigadier Paul Lewis, drove to Liwonde to confront the rebels who then retreated to their forest bases.

Seven were reported captured and three shot dead with no trace of Chipembere’s whereabouts.

Two months later, Chipembere was secretly evacuated with full knowledge and approval of Banda to America through a deal negotiated by the US Ambassador Sam Gilstrap and Governor-General Sir Glyn Jones. In the US, he studied for a masters at the University of California in Los Angeles.

He returned to Africa in 1966 and briefly taught at Kivukoni College in Tanzania while trying to revive his political activities by forming the Panafrican Democratic Party (PDP) with no tangible success.

This left him with no option, but to fly back to America to work on his PhD while teaching Modern and Contemporary African History at the same old university.

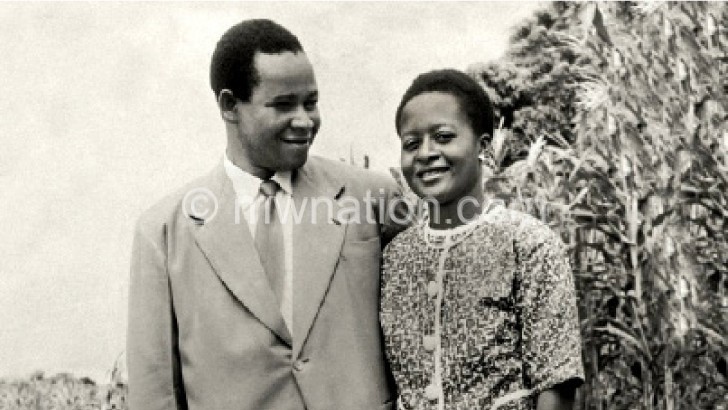

Chipembere died of diabetes in America on September 24 1975 at the age of 45. He was survived by a wife, Catherine and seven children.

Over a long time, members of his guerrilla army in Malawi were hunted, arrested, surrendered, tried, convicted and executed.

A handful escaped to Zambia and Tanzania while his elder brother Arthur, former parliamentary colleague George Ndomondo and others languished in jail for years.

The big catch for Banda was Silombera after several months of hit-and-run tactics killing some Malawi Congress Party (MCP) local leaders and a chief in Mangochi and Machinga districts.

He was arrested, tried and earmarked for Malawi’s first (public) execution.

He was secretly hanged amid pleas for clemency from abroad and prominent political figures, including Banda’s long-time ally, Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana.

Records reveal that apart from Silombera, eight others accused of murdering Police Inspector Changwa’s wife were executed at Zomba Central Prison after almost a decade of detention without trial. n

(Willie Zingani is a veteran journalist, researcher and author.