Communities lead in sanitation, hygiene

Aisha Rajab, 30, lives next to a shabeen in Said Village, Traditional Authority (T/A) Ndindi, Salima.

The woman and her three children have no problems with their neighbour Tiyankhulenji Kambalame, 24, except the conduct of her drunken customers.

Recently, there have been tensions between them because of drunks from the joint who often urinate just outside Rajab’s house.

“We cannot continue living like dogs,” she says.

Rajab has had to wash the walls of her house and a shared pathway to get rid of the pungent smell and to make the area safe and hygienic.

She is worried about the health of children who often play on a bare space she shares with the neighbours. This is where the drunks urinate willy-nilly. Yet the children use this space as a common playground since not many houses have similar yards.

When Rajab complained about reckless urination to community leaders, they reprimanded Kambalame and ordered her to construct pit latrines and urinals for her customers.

“Health surveillance assistants [HSAs] and community leaders had been advising me to put in place pit latrines and other sanitation facilities, but I was reluctant,” she explains.

Such was the wave of resistance from the start of the business that angry neighbours painted a warning on the wall, urging against the tendency of urinating on the wall or in the open.

According to the warning sign, they were supposed to use a public toilet situated along the footpath.

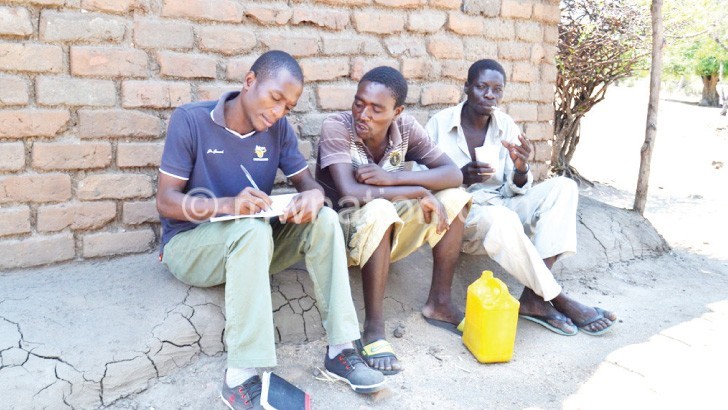

Neighbourhood policing forum members were deployed to ensure no imbibers defied the community resolution. Robson Mangwere, HSA for Ndini area, says the lack of personal and domestic sanitation and hygiene facilities has catalysed diarrhoea and other diseases related to unsafe water as well as poor sanitation and hygiene.

Now, the community has developed a strategy to reduce cases of waterborne and sanitation-related diseases, working hand in hand with a German Organisation, Welthungerhilfe (WHH).

They have formed health clubs for improved hygiene and nutrition in villages where many people used to urinate and defecate in the open.

Through the clubs, the project insists on a participatory approach to increase access to hygiene and nutrition education project in T/A Chauma in Dedza as well as Maganga, Ndindi and Pemba in Salima.

WHH with funding from GIZ is equipping communities with necessary skills for developing innovative approaches and technologies for radical and sustainable improvements in sanitation in their homesteads.

“Our participatory approach, through community health clubs, was developed as part of a consultative and integrative process aimed at establishing a hygiene promotion strategy that gives the power to the community,” says Percy Chiphanda, WHH field coordinator in Salima.

The strategy offers community members the power to play a leading role when it comes to decision-making, promoting feasible sanitation, hygiene and nutrition solutions as well as making each other accountable.

Chiphanda’s organisation believes there is need for government to work together with beneficiaries to achieve equitable sanitation and hygiene.

The community change agent advocates community involvement and participation, with the Ministry of Health officials providing supervision and controls.

In the country, authorities require public places to have adequate sanitation and hygiene facilities.

However, the provision, use and monitoring of these facilities is not always obvious, especially in informal settings such as shebeens.

Ministry of Health chief director Chimwemwe Banda says it is government’s wish that essential sanitation services are available to all Malawians regardless of where they are.

The government official wants sanitation facilities to be acceptable, accessible and affordable for all across the country.

But many communities and homesteads are constrained by poverty.

Even government does not have adequate resources to provide requisite trainings and mass awareness on the importance of basic sanitation and hygiene.

“Government, therefore, welcomes and appreciates efforts by various partners, including WHH to address challenges existing in the water, sanitation and hygiene sector,” she says.

According to participatory health and nutrition education facilitator Sefu Sibale, the project is not only eliminating sanitation and hygiene concerns in homes but also in rural drinking joints.

He says the development process was grounded in a solid understanding of the problem and community needs, the relevance of community participation and a desire to work together to overcome it.

With increasing awareness, both the shebeen owners and customers are increasingly insisting on clean sanitation facilities for their wellbeing.

The consensus to stop urinating and defecating in the open has led to a drastic reduction of waterborne diseases. Many households in Ndindi own and use latrines.

“Following the introduction of the participatory approach, we successfully reduced the incidence of waterborne diseases by over 70 percent in 2015” Mangwere says. n