Does land use planning work in Malawi?

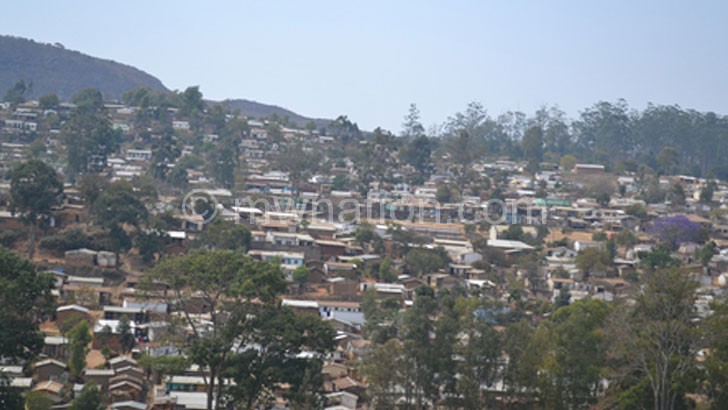

Five years ago, residents of Mchengautuba Township in Mzuzu had a rude awakening.

In a blink of an eye, about 20 000 people of the high-density township found themselves at loggerheads with Malawi Housing Corporation (MHC) over land ownership.

MHC claimed the locals had encroached its land. And it vowed to repossess all the encroached land. Alternatively, the inhabitants were asked to pay MHC if they wished to continue possessing the land.

But the locals protested the move and challenged the matter in court.

“My people have lived in Mchengautuwa long before MHC had offices in Mzuzu and too long before they came with their so-called plots in 2013.

“Mchengautuwa does not belong to Malawi Housing Cooperation as it is being alleged. As Mchengautuwa community, we have taken this strong stand with cognizance of the facts which make us a conviction that our rights as people whose land is being grabbed are being violated.

“It is our view that our poverty should not be a premise for persecution, we remain proud of the land that we treasure and it will remain our most important resource and that should be respected,” argued the villagers in an affidavit.

That was in July 2014.

Coincidentally, in the same month and year, Blantyre City Council (BCC) demolished about 200 “illegal” residential structures at Mpingwe Hill in Limbe.

The council conducted the exercise under the supervision of MHC as purported owners of the encroached land.

These are just examples of the numerous encroachment cases registered across the cities.

In Lilongwe, residents of Baghdad in Area 49 also met the same fate around the same years as their houses were demolished on a 120-hectare piece of land.

Although such exercises are backed up by the Physical Planning Act, experts agree that the demolitions are a reflection of a failed planning law in the country.

Argues Mzuzu University (Mzuni) urban planning lecturer Dominic Kamlomo: “Demolitions or evictions are commonplace in Malawian cities. But the large proportion of the rich and powerful go scot free.

“The demolitions usually target the vulnerable groups. So, the planning law in Malawi is used for enhancing the value of land owned by the rich while the disadvantaged are subjected to demolitions.”

Historically, planning was used to constitute and control the resource of developable urban land and to ensure that towns and cities developed in ways that maximised the public benefit.

In Malawi, planning was used by colonial regimes to assert the interests of a small minority over those of the majority. Planning Law in Malawi has changed twice since independence, in 1988 and 2016. However, the law has been designed based on British law; a rather inappropriate blueprint for present day Malawi.

Kamlomo says planning through its laws is supposed to regulate land use and land development, provide a basis for infrastructure planning, to secure the rights of investors, to protect environmental resources and mitigate environmental risks.

“Planning law must help to determine which buildings are legal and which ones are not. Planning law is, therefore, meant to reflect and assert the public interest. This is not the reality in Malawi though. Land use is largely unregulated. Integrated infrastructure planning is rare. Private rights and interests are not mediated by a comprehensive legal framework.

“Land use planning is meant to empower society socially and economically, however, without meaningful grassroots participation in land use planning the effectiveness of planning can remain an illusion.

“Urban management is very erratic and fragmented. There are very beautiful plans for our cities but ironically, the overwhelming majority of buildings are constructed in contravention of planning,” he says.

Kamlomo says apart from the demolitions, there are two more indicators of failed planning in urban centres. He says the predominance of illegal structures and impunity by the rich and powerful are the other indicators.

In order to bring about sustainable planning laws, Kamlomo suggests that citizens must determine the characteristics and growth of their cities.

He says urban planning and other laws must influence these patterns of development.

Architecture and urban affairs doctorate student at Virginia Polytechnic in the United State of America, Amos Kalua, agrees with Kamlomo that the general public, as a key player within the industry, must be widely empowered to question decisions that are made by the development control authorities where things appear to be going south.

“It appears that there exists very little synergy between the multiplicity of players within the built environment industry. It is important that the little synergy that is there during the production of the city plans goes all the way to the implementation and monitoring,” he says.

Kalua, however, observes that authorities have been put at a tight corner to enforce planning laws due to the frequent disasters induced by climate change.

“We have seen how over the years human activity is causing soil erosion which is creating gullies where none existed before and eating away from river banks and turning once habitable land into marginal land. With climate change, such phenomena are hard to anticipate ahead of time. The authorities may be left with two options, either to abandon the plans or stick to them, surely and sadly, at a major cost to the general public,” he says.

Kalua’s observation comes at a time the preliminary results for the 2018 Population and Housing Census indicate that Malawi’s population density—number of people per square kilometre—continues to grow while the land area remains static.

The census found that Malawi’s population density stood at 186 persons per square kilometre up from 138 in the 2008 census, representing a 35 percent jump. This implies that more people are in need of land in cities.

But Mzuzu University (Mzuni) physical planning expert Mtafu Manda observes that density in cities “is very low”, and it wouldn’t sound logical to link population boom to problems of land planning.

He says the issue still boils down to failure by authorities to enforce the planning laws.

“For example, the plan for Mzuzu emphasises building vertically. Unfortunately, developers have some fear to build high and city councils also don’t encourage people to do so.

“Even new buildings coming after the plan are still only ground level like village groceries. For some reason, each one claims not to be aware even when such buildings are constructed in front of their offices,” he says.

As Manda argues, what it means is that the planning law in Malawi favours the rich and the powerful. n