Exclusion water Cholera

The cholera outbreak in the capital city has exposed how Lilongwe Water Board (LWB) has forsaken a community in the shadow of its headquarters, our News Analyst SUZGO CHITETE writes.

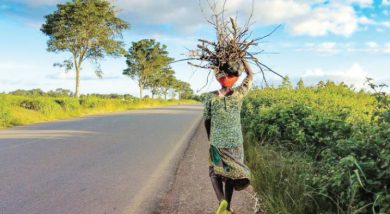

Mitengo is a small village within Area 36 in the capital, Lilongwe. Situated along the City West Bypass Road, the little known slum overlooks Madzi House, the headquarters of LWB.

Ironically, the area has no safe water. The densely populated spot has been hit hard by the raging cholera outbreak that has affected 770 and killed 24 in the country. Lilongwe has registered 13 deaths and 250 cases.

‘It killed my child’

Minister of Health Atupele Muluzi has named use of unsafe water from streams and wells as the main cause of the outbreak which has laid bare deep-rooted inequalities between the haves and the have-nots.

“Thank God, I survived. I thought it was just diarrhoea. Knowing that there was a cholera outbreak, we rushed to Bwaila Hospital where I instantly got the medical assistance,” explains one cholera survivor in Mitengo.

He refuses to be named to safeguard “myself and my family from embarrassment” associated with the disease linked with poor hygiene.

During the visit, the man took us throughout the village, pointing at shallow wells where the low-income earners draw water for domestic use.

Together we visited a family which lost a child to cholera. The deceased’s mother was seen pouring boiled water into a bucket. She covered and took it inside the house. Two metres away, a lonely boy, about eight years old, was playing with no one really—scribbling its babyhood thoughts.

“Cholera has robbed my child of a sibling and a playmate,” the woman said, boiling some more water.

For her, boiling water, even from LWB, has become a way of life since cholera hit her household.

“My child didn’t have to die of cholera,” she said. “Hospital staff told us it was because of the bad water we take. They told us to stop drinking water from shallow wells and streams, but our problem is that we do not have access to taps.”

Truckloads of water

To contain the outbreak, LWB’s bowsers supply Mitengo with safe water twice a day.

When he toured Mitengo Village three weeks ago, Muluzi said it is shocking that the poor city dwellers still rely on shallow wells and streams for drinking water.

“We have learnt that the biggest problem is lack of safe water in these areas. Going forward, we have to ensure that we provide safe water through Lilongwe Water Board as a long term prevention strategy. This will minimise the cost of treating cholera,” explained the minister.

Muluzi said LWB will establish water kiosks in the area left behind.

When pressed how this area remains excluded from the capital city’s water pipeline, the minister said everything general about government plans and nothing specific about how the community remains at the receiving end of unsafe water.

A deadly awakening

“We are engaging relevant government ministries and departments responsible for provision of water to lessen the disease burden. We are doing our part as a ministry and we need to engage other stakeholders,” he explained.

This subtly confirms the lack of water at Mitengo and other parts of Lilongwe is due to failure by other government agencies.

The cholera situation has exposed how failure to provide safe water for all pushes people to preventable deaths.

Just a stop-gap

The deployment of water bowsers is just a pain killer, not a permanent game changer.

In an interview, LWB spokesperson Trevor Phoya termed the cholera mitigation strategy “just a temporary initiative” while awaiting a long-term solution.

LWB spends about K80 000 per trip for a water bowser to deliver the precious commodity to the needy community, according to Phoya.

To serve Mitengo residents twice a day, it drains K160 000. This translates to about K5 million per month.

While Mitengo and other congested urban areas are deprived of safe water, peri-urban areas, such as Area 50, Kauma and Mtandire, have access to safe water through kiosks managed by water users associations.

This could be more the reason cholera-prone zones in Area 50 (Senti and Mtandire) have gone without serious cases this time.

Nobody’s zone?

According to LWB Kiosk Unit manager Edward Kwezani, Mitengo lies outside their catchment.

Asked why they are providing water bowsers when it is outside their focus area, he changed tune:“It is an emergency and we thought we needed to intervene.

“But as a permanent solution, we will surely consider connecting the area.”

In the current national budget, government allocated K12 billion for improving water supply in all 193 constituencies.

Safe water for all

Lilongwe Central member of Parliament Lobin Lowe argues that the topography of Mitengo makes it difficult to sink boreholes.

He blames Capital Hill for lacking strategies to connect all parts of the city to safe water in line with sustainable Development Goal (SDG) six which President Peter Mutharika and other world leaders adopted in New York September 2015.