Fishing out Chia’s illegal nets

All is not well for Owen Banda, 54. The catch of the fisher at Chia Lagoon near Lake Malawi in Nkhotakota has shrunk by almost 80 percent.

Years ago, Banda used to catch about 5 000 fish a day, he says. But now, he sometimes catches just about 300.

“My fish catch has gone down in recent years and this has affected my earnings. I struggle to pay school fees for my children,” he says.

Illegal fishing, coupled with population growth, climate change and deforestation, threatens fish stocks in the country’s largest lagoon, the freshwater lake and other water bodies.

According to chief fisheries extension officer Albar Pulaizi, the future looks uncertain as the population of fish, especially chambo, has fallen drastically.

The Department of Fisheries estimates that fish stocks in the continent’s third-largest freshwater lake have dwindled by 90 percent over the past 20 years.

This is bad news for Banda and about 1.5 million Malawians who depend on fish for animal protein.

“The fish stocks have declined in the last two decades from about 30 000 metric tonnes per year to 2 000 per year. But this may get worse if illegal fishing is not fully checked,” Pulaizi warns.

Ripple Africa chief executive officer Geoff Furber fears the scarcity of fish will have devastating effects on poor households that wholly depend on fish.

“Overfishing and increased economic activity are depleting the fish stocks in Lake Malawi. This problem has major economic and environmental consequences for the future of Malawi and other countries around the lake,” he says.

The need to stop the loss of fish species looks urgent.

The 3000 families surrounding Chia Lagoon mostly subsist on fishing.

“We know that unsustainable fishing practices and non-compliance with fishing regulations have depleted the fish stock,” says Traditional Authority (T/A) Mwadzama for the area.

The locals are working closely with Ripple Africa to roll back challenges hampering the conservation of fish species in Lake Malawi and neighbouring fishing grounds.

According to Mwadzana, anyone found in breach of community-led by-laws is banned from fishing in the lake.

For five years, the village development committee have been educating the locals about the bylaws and the need to protect the lake.

“Apart from protecting the fish, we also want to safeguard the water so that it’s safe for drinking. We create awareness at gatherings, such as weddings and funerals,” says committee chairperson Owen Kasache.

For years, there has been a ban on the use of high-yield fishing gear in Lake Malawi between October and November, when the fish spawn.

In 2003, government launched a 10-year strategic plan, which largely seeks to restore the lake’s fish stocks.

For the last 10 years, communities around Chia have been re-introducing into the lake fish bred outside the lake.

“We haven’t done badly,” says Pulaizi, unsure if this had significantly increased the lake’s fish population.

Nonetheless, villagers in Nkhotakota now understand that the future of the lake is important.

They are educating those who can do something about it.

With support from Ripple Africa, they have formed 60 fish conservation committees to enforce the fisheries by-laws in the area.

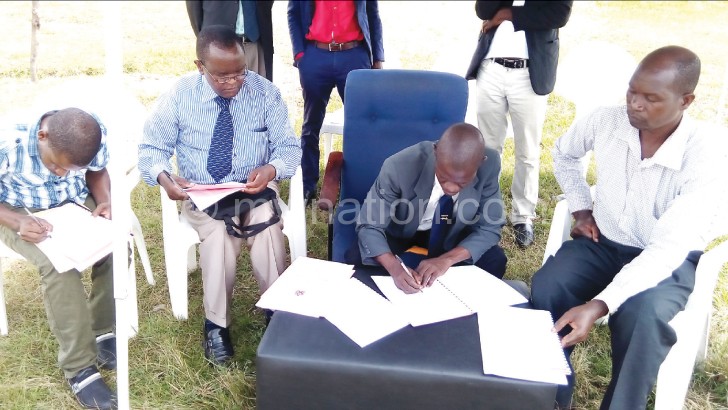

“The official signing of the by-laws means that we are ready to bring to book anyone who will be involved in unacceptable fishing practices,” vows T/A Mwadzama.

So far, the committees have confiscated 10 000 mosquito nets fishers were using to catch small fish.

“The most important message for all fishing communities in other areas of Malawi is that if they want to catch more fish in the future and make more money, they must work together to stop the use of mosquito nets for any type of fishing and allow the fish to breed and grow,” added Furber.