Gunfire gives way to hope in Malindi

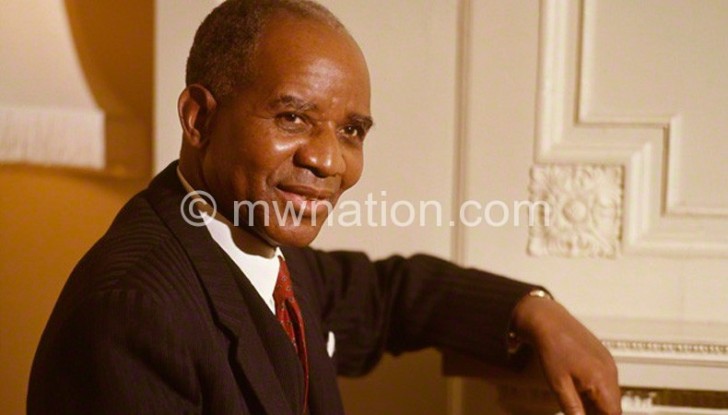

Matiya Cecil Chiweza is a man of many talents. And secrets too: he is known in the adjacent villages of Steveni and Makwinja in Malindi, Mangochi District, as a skilled repairer of broken down bicycles and leaky roofs.

Some also know that he is a qualified bookkeeper, up to final accounts. But many would be stunned to learn that this affable man is also a veteran in guerrilla warfare and that he was detained for many years as an enemy of the State.

I found out about him while making enquiries on the armed revolt that Masauko Henry Chipembere had launched in Malindi against Malawi’s founding president, Hastings Kamuzu Banda.

Much has been written about Chipembere. Historians regard him as the architect of this country’s independence in 1964, for having summoned Banda home from exile to lead the country’s anti-colonial battle.

Chipembere, however, alongside Kanyama Chiume, Yatuta Chisiza, Willie Chokani and other Cabinet colleagues, fell out with Banda in what became known as the Cabinet Crisis of 1964, just two months after independence.

Very little, however, is known about people like Chiweza. He was among the foot soldiers of Chipembere’s army.

“That uprising happened 62 years ago,” Chiweza told me. “It was an effort to try to free our fellow Malawians from tyranny.”

Chiweza was among hundreds of young men who joined a rebellion that might have changed the course of Malawi’s post-independence history.

But Chiweza was no ordinary insurgent. “Chipembere was also my uncle,” he revealed to me. “He put me through school and brought me up in his household.

“I was also his chauffeur. I used to drive him and other family members around in a distinctive cream-white Mercedes Benz around Blantyre, Zomba and Mangochi. I knew what he felt and hoped for the new nation of Malawi. So, when he launched the war, I joined him without any hesitation whatsoever.”

Chiweza first met Chipembere in 1950 when he was six years old. Chipembere was then a district commissioner at Domasi near Zomba.

His grandfather, who was Masauko’s father, was Canon Habil Chipembere, a priest in charge of St Martins Anglican Church at Malindi.

His grandfather had brought him to Malawi from their original home in Mozambique, which was then a colony of Portugal.

“The Chipembere family originated from Chiwanga Village in Matengula which lies east of Lake Malawi,” explained Chiweza.

After completion of primary education at St Martins Primary School in Malindi, his uncle, Chipembere, took the young Chiweza with him to Blantyre.

He was brought up in a large house at Mpingwe. The families of Chiume and Chisiza also lived in the house.

They were erstwhile friends who also shared the same ideals with Chipembere over the future of the new and supposedly, to become the democratic State of Malawi. “I was in a camp that ‘Uncle Chip’ set up with about 600 guerrilla fighters,” Chiweza told me.

“It was code-named ‘Camp Zambia’ and it remained hidden in thick jungle behind the Kasomali Hills,” Chiweza explained.

The Kasomali Hills are a towering landmark at the back of a picturesque bay that distinguishes Malindi on the southeastern side of Lake Malawi.

It takes about 20 minutes to reach Malindi from the centre of Mangochi, after turning left, off the Bakili Muluzi Highway that leads to Namwera.

Chiweza painted a fascinating picture of life in Camp Zambia: “We were trained in the handling of weapons and explosives. Fellow Malawians provided the instructions. ”

One of these was Medson Evans Silombela who was later captured by the security forces and executed in Zomba.

This was after a sensational trial in the High Court of Malawi, that I had coincidentally covered when I was a young reporter at the Daily Times newspaper in Blantyre.

“We were not engaged in any fire-fights with the security forces or with Banda’s Malawi Young Pioneers.”That was a youth movement that had degenerated into a terror militia to prop up the Banda regime.

The Malawi Army destroyed it in 1993 after some of its members picked up a fight with its soldiers.

“We sharpened our skills in the use of fire-arms, hand-to-hand combat, ambushes, guerrilla tactics, logistics and other skills in readiness for a special mission,” said Chiweza.

That mission was launched on the night of 12th February 1965. It was aimed at taking over the country.

Chiweza was in a group of about 200-armed fighters, led by Chipembere, who attacked the town of Fort Johnston, which was later named Mangochi.

They reached the town after crossing the Shire River in a flotilla of boats and canoes.

“Our attack on Mangochi was accompanied by much whooping and screaming of our war cry: “Okello!”

This was a code word that was intended to alert sympathetic black policemen who were under the command of white expatriate Britons, to surrender and hand over their weapons and ammunition to the rebel force.

“We took lots of guns and ammunition,” recalled Chiweza, “before we drove off that night in three trucks, headed for Liwonde on our way to Zomba which was the seat of government,” he said.

“Our mission was to launch a surprise attack on the main barracks of the Kings African Rifles (KAR) in Zomba and force Banda and his government to surrender.”

When the group arrived at Liwonde, however, they discovered that a ferry that was manually operated to carry vehicles and peoples across, was moored on the other side of the river.

“We called out to the ferry operators to come over, but just as they were about to do so, a Land Rover with British expatriate and black police officers drove up.

“They ordered the ferry crew not to cross over with the ferry to our side of the bank,” said Chiweza. “The crew shouted back that they would come to us only after sunrise.”

Some of the guerrillas wanted to commandeer the ferry by force, but Chipembere advised against it, explained Chiweza.

This was because Chipembere realised that the planned attack on Zomba had lost its surprise.

When the group hit the Fort Johnston police station, someone had managed to escape and alert the KAR in Zomba about the attack.

Chipembere therefore had no choice but to retreat with his men to ‘Camp Zambia’, which had still not been located by the security forces.

In retaliation for the attack, however, the security forces launched a war of attrition in Makwinja and other villages in Malindi.

They swept through Malindi, setting fire to homes and up to Makanjira, which lies about 90 kilometres north of Malindi.

Chipembere’s home at Malindi was the first to be blown up with dynamite and reduced to rubble.

“They slaughtered goats, cattle and chickens and arrested every able-bodied man for information on the whereabouts of Chipembere and the rest of us,” said Chiweza.

Listening to his tale, it was hard to imagine that so much violence had taken place just a short distance away from the comfort of the verandah of my beach house where Chiweza and I were chatting and sipping cold drinks.

“They also burnt down Taliya Village which lies about 10 minutes drive from Makwinja Village towards Makanjira,” he explained.

After the destruction of Taliya Village, Chipembere advised his men to abandon Camp Zambia and set up a new hideout, deep in the hills of Namizimu Forest at Lugola in the Makanjira vicinity.

At this stage, two important developments were taking place. One was that Chipembere, out of concern for the safety of his men as the security forces were closing in, ordered many of the guerrillas to return in secret to life in the villages.

The other was that secret negotiations were going on between Chipembere and Banda through high level emissaries of the American and British governments for an end to the insurrection and security operations.

The Americans, as self-styled leaders of the western world, were locked in the so-called Cold War that pitted capitalism against communism.

They and their western allies were apparently worried over the real possibility of Malawi, one of their client states, falling under communist influence should Chipembere’s rebels have forged an alliance with communist-trained and backed nationalist fighters who were then making incursions into Mozambique, Zimbabwe and South Africa.

Malawi’s neighbouring states, Tanzania and Zambia, had by then already embraced socialist ideologies.

Tanzania was practising Ujamaa, a form of social and economic ‘family hood,’ while Zambia was experimenting with so-called ‘African Socialism,’ which placed emphasis on sharing resources in a traditional way.

A secret deal was thus struck with Chipembere to disband his guerrilla army. In return, he was assured safe passage out of Malawi and a position at the University College of Los Angeles, UCLA in California.

Chipembere informed Chiweza and the rest of his fighters about this. “He told us that he might be leaving the country,” said Chiweza. “He also advised us to find a way out of the camp and to disperse secretly and quietly to civilian life.”

Chipembere settled and taught at UCLA in California, where he died in 1975 of illness.

Chiweza, like many of his fellow comrades-in-arms, went underground, and held on, until now, to the many secrets of his uncle and the uprising.

He assumed a new identity; making ends meet by repairing roofs and bicycles in various villages in Malindi and Makanjira.

But five months later in July 1965, the game was up for Chiweza and several of his comrades-in-arms.

They were arrested after a government informer who knew him from school days, spotted him and tipped off the authorities.

Then followed years of detention without trial in the Zomba Maximum-Security Prison, followed by transfers to the infamous Dzaleka Maximum-Security Camp in Dowa District.

“We were kept in degrading and humiliating conditions at Dzaleka,” said Chiweza.

Banda eventually released Chiweza and his colleagues from detention six years later under an act of clemency on Martyr’s Day.

Some of his fellow-rebels had already been shot dead by the security forces; others died in political detention camps while just as many succumbed to natural causes, including advanced age.

Chiweza says he holds no bitterness over the past. Like millions of other Malawians, however, he expresses disquiet over how successive leaders after dictatorship, have failed to pull the country out of its poor economic and political position.

Now a genial grandfather who looks remarkably younger than his 71 years, he is possibly the only remaining survivor of that bloody chapter of Malawi’s history.

On his part, Banda who died of illness in November 1997declared that he would never forgive the people of Malindi and Makanjira for having supported Chipembere and his rebellion.

True to his word, Malindi and Makanjira remained dormant for decades with no State-funded projects, of any kind.

The western co-operation partners also showed no inclination to provide any assistance for the recovery of Malindi and Makanjira.

Infrastructural developments such as the Lakeshore Road and privately financed capital for resorts were confined to the opposite side of the Lake.

Investors and holidaymakers were simply too afraid to go to Malindi, even after the end of single party dictatorship.

Ironically, Malindi has St Michael’s Girls Secondary School, which over the years has churned out some of the country’s best students who have gone on to become bankers, medical doctors, high court judges and others playing key roles in Malawi’s development.

Malindi also boasts, in St Martins, one of the best rural hospitals in Malawi and like the school, is funded not by the state, but by the Anglican Diocese.

Malindi’s first sign of change after the end of Banda’s dictatorship, was introduced by the administration of President Bakili Muluzi’s United Democratic Front, UDF, when he was elected to office following Malawi historic multi-party elections in 1994.

The UDF honoured Catherine, the widow of Chipembere, with a Cabinet position after she was elected to Parliament on its ticket.

In addition, it initiated the construction of a tarred road, albeit a single narrow lane that turns off from the Bakili Muluzi Highway but ending 30 kilometres after Malindi.

Drivers play a dangerous game of chicken on the narrow lane, waiting until the last possible moment, to see who blinks first and gives way to the on-coming car on the narrow tarmac lane.

They also have to compete against cyclists, cattle and goats on narrow, rickety wood-and-metal Bailey bridges that were constructed by the British during World War II.

Besides the hospital, only three large beachside houses have been constructed at Malindi.

One of these is a beautiful, Dutch-colonial design in white, by a non-governmental organisation that promotes international research projects and rural-based tourism.

More meaningful change is now on the horizon. This follows an announcement by the Democratic Progress Party (DPP) administration under President Peter Mutharika that China is to finance the construction of a full tarmac road from the Mangochi turn-off through to Malindi and up to Makanjira. The project is scheduled to begin in a few weeks time, this March. It has generated much excitement, with expectations of new opportunities of employment.

It holds out the hope of closure of decades of violence, poverty and isolation and the opening of a new chapter of a better life for the villagers of Makwinja, Steveni and others in Malindi and Makanjira.