Heatwave threatens tea yields, livelihoods

Tea is rated as the country’s second major foreign exchange earner after tobacco.

Last year, revenue from the crop was $16.1 million (about K12 billion), according to Reserve Bank of Malawi while in 2017, the commodity wired in $14.5 million (about K10 billion) in foreign exchange earnings.

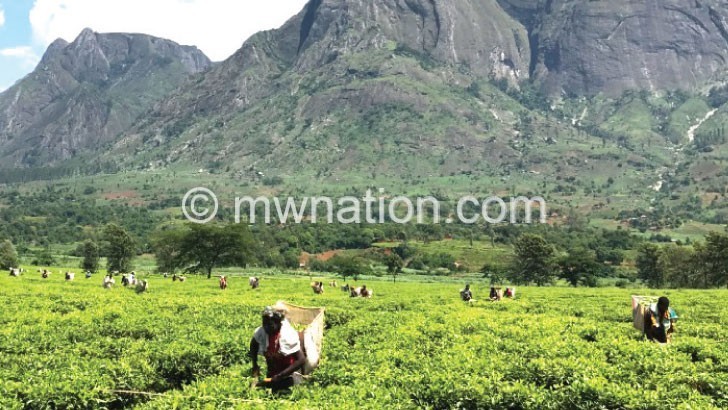

Besides bringing forex, growing tea provides employment and contributes to the livelihoods of many men and women in the country.

Statistics indicate that there are 18 500 smallholder farmers and many more are employed as seasonal farm workers or tea pickers.

However, the future looks bleak this year.

The Future Climate for Africa (FCFA) programme has released a 12-minute film highlighting how the heatwave experienced in the country last month threatened tea yields and livelihoods for growers in Mulanje and Thyolo.

According to the documentary, released last week, the result of the heatwave has been that the leaves of tea bushes—which are what is harvested from the crop—turned brown and shrivelled.

Tea Research Foundation of Central Africa senior agronomist Chikondi Katungwe says there are a number of factors to be considered when growing tea.

“The main ones are rainfall and temperature. Tea requires about a minimum of 1 200mm of rain per annum and the ideal temperature ranges between 12.5 degrees Celsius and 35 degrees Celsius,” she says in the documentary.

However, two weeks ago, the Department of Climate Change and Meteorological Services (MET) said Mimosa Weather Station in Mulanje, one of the tea growing districts in the country, recorded temperatures exceeding 35 degrees Celsius and as high as 40 degrees Celsius during a 10-day period late last month.

Observing weather changes

Austin Changazi, general manager of Sukambizi Association Trust (SAT), an organisation of small-scale tea producers in Mulanje, says he has lived in the area for the past 29 years and he has seen some changes in the weather patterns.

“We have seen fewer months of rain. So, in the smallholder sector, it has been a big problem and as a result, production in tea fields has gone down,” he says.

A smallholder farmer in Mulanje, Princewell Pendame, felt the pinch of the high temperatures experienced.

He says: “Because we have high temperatures, we are having a lot of difficulties in raising up new crops. Most of the tea will even die because of high temperatures. Things are not okay.”

While these challenges are enough to leave the tea growers worrying, they (the challenges) are also worsened by the fact that tea requires long term planning.

“The economic life of a tea bush is at least 60 years. If you plant today, it will take about three to five years for the field to get established, but then for you to get the economic yield it takes about seven to nine years,” says Katungwe.

This long economic life of tea plants means decision-relevant information around potential future climatic changes is important to inform investment as well as adaptation planning.

Solutions

Recognising the need for this information, FCFA programme has been working in Malawi and Kenya on a project called Climate Information for Resilient Tea Production (CI4Tea) which works in partnership with tea producers to produce tailored climate information for the tea-producing regions in the two countries.

The project also aims at exploring potential adaptation options for supporting medium and long-term planning in the tea sector.

CI4Tea project primary investigator Professor Andy Dougill, from the University of Leeds, says the project came about because of the recognition that they produced climate briefs for what the future climate of Malawi might be like, but in very general terms, just in terms of average temperature and average change in rainfall.

“And what we recognised was that we needed to tailor that information to specific metrics—what were the things they could see that were starting to affect tea production now and what are the research stations preparing for in terms of the climates in the future,” he says.

To generate the most appropriate and decision-relevant information, a new set of climate metrics were developed, and they included information such as the number of consecutive hot days or rainy days that would affect tea production and quality for specific seasons or months.

One of the early challenges was finding reliable data and at the specific scale required.

CI4Tea project research fellow Dr Neha Mittal, also from the University of Leeds, says the information that climate models provide are at a grid scale, which is much larger than a local scale at which information is actually required.

“So, to generate knowledge at a local scale, we have used a novel approach of combining station observations, global climate model projections and projections of high resolution convection-permitting models for Africa, which is called CP4A.

“We have tailored the future climate projections to capture location-specific responses for the future for Malawi and Kenya,” she says.

MET chief agrometeorologist Charles Vanya says having a dense network of stations in most areas is going to help, because it will address the local variability which is the main driving factor of weather and climate in Malawi.

To overcome some of the challenges, and to help create climate models at a scale never seen before in the region, the project has been working in a collaborative way.

Says Dougill: “It builds on strong in-country collaboration links we have, both with universities and with the MET services in both countries, and what has been added is the close collaboration with the research stations in both countries and also with the tea producers and the smallholder associations themselves.”