How Washington Consensus impoverished Malawi

You may have heard about the Washington Consensus. If you have not, please maintain your ignorance because those of us who know, economists, development specialists, social change experts and development communication gurus, are justified to be angry, very angry indeed.

Crudely put, the Washington Consensus refers to policies promoted by three institutions, the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund and the US Treasury based in Washington, District of Columbia, United States of America.

These three institutions have been responsible for damaging, worsening poverty and encouraging corruption in already poor countries. We know this because we are consumption economists. Ours is economics of the basket, of the pocket, and the table. Ours is not gross domestic product (GDP) economics. Neither is it gross national income (GNI) and other fashionable but useless terminologies.

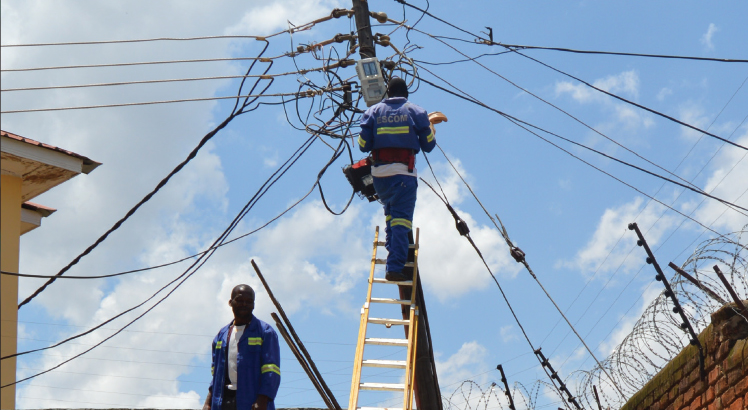

To us, the economy is fine when the majority can find jobs, get paid a decent wage, be able to buy food, afford fuel, send children to school, be able to save some money, and build or buy a home. To us, the economy is fine when a country has good road infrastructure, clean environment, has unfettered supply of power for lighting and cooking, has water for drinking, washing and bathing. To us, an economy is growing when the people feel they are growing, are succeeding and can afford a smile.

Despite the oppressive politics of the time, most African economies were at least stable, or growing and making their people happy until the Washington Consensus gang convinced the economically-deficient new leaders to abandon State control of the economy and leave it in the hands of the private sector, to devalue the currencies and to stop subsidizing consumption. Those who refused, majorly South Africa and Maghreb Africa, continued to have stable economies until the Americans, British, and French sponsored disruptions and wars there in the 2010s.

These structural adjustment policies (unpopularly known as SAPs) wrought the worst misery on African citizens as their economies started crumbling. In Zambia, whose new president, Frederick Chiluba, quickly embraced the SAPs, the national currency, the Kwacha, tumbled so much so that it was rendered virtually useless. For some time, while Ngwazi Kamuzu Banda was still power, the Malawi currency stood strong but when Ngwazi Bakili Muluzi took over and accepted the Washington Consensus economic policies, the Malawi Kwacha started its nosedive depreciation until when Ngwazi Bingu wa Mutharika came in and told the Washington Consensus off.

Because the economy was being privatised, the politicians started and registered companies which won almost all government tenders and contracts. Bribing to win a tender was not uncommon. Politicians flocked to the ruling party to eat the pie. Politics became the nouveau enviable limited company (Pty) and politicians became the new oligarchs of Africa.

In the frenzy, even successful companies were sold off. Sugar Company of Malawi (Sucoma) was sold off to Illovo, thus taking the profits to South Africa. While Malawi provided the soil, the water, and the human resource, South Africa got, and still gets, the money.

Malawi Posts and Telecommunications (MTL) was unbundled to create Malawi Savings Bank, Telecoms Networks Malawi (TNM) and Malawi Posts Corporation. Malawi Savings Bank (MSB), with outlets in all districts and rural outposts, was sold to FDH, taking with it millions of kwacha in ordinary people’s small savings. Today, economists cry, crocodile-like, that the rural people are unbanked. How can they be banked when you took away the people’s bank and gave it to an individual, almost gratis? What have the ordinary people gained from the sale of MSB?