Lawi romanticises village life to poisonous levels

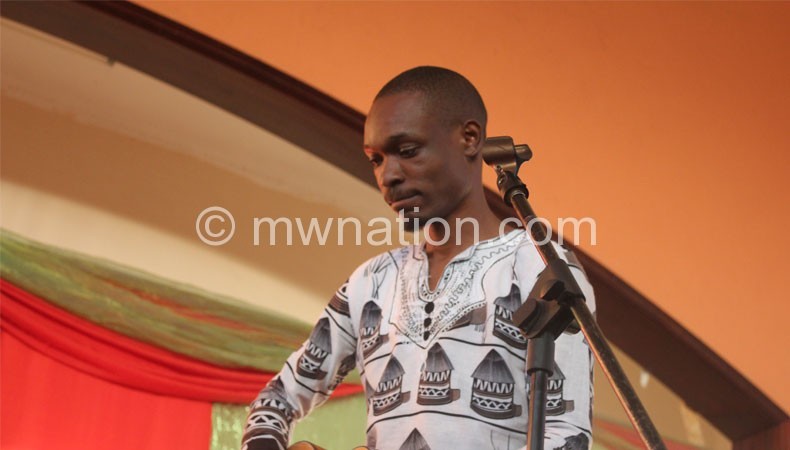

Many people would agree with me that in the year just ending Lawi—and his eponymously named album—was a huge sensation on the Malawi music scene.

For me, Lawi is the next ‘big thing’ to have ever happened on the Malawi music scene after Mte Wambali Mkandawire, Evison Matafale and Peter Mawanga.

I was initially disappointed by what at that time was Lawi’s most popular song, Amaona Kuchedwa, which I thought, was more of ‘Alan Namokoish’ both in instrumentation and vocals.

That is my (biased?) opinion, anyway. But eventually, after I had taken time to listen to the whole album, I fell in love with, among other things, Lawi’s nostalgic touch in what I have taken to calling his ‘Songs from the Mango Tree.’

Nostalgia runs through such songs as The Whistling Song, Lilongwe, Africa and Life is Beautiful.

Life is Beautiful is a song I immediately fell I love with the first time I listened to it. The song celebrates so-called typical life in a typical Malawian village. Day breaks with the cock in chorus with birds of the wild.

Women, men and children are up and about in footpath criss-crossing the countryside, hoes on their shoulders, supposedly heading to their farms. There is laughter in the air as people greet each other good morning.

At midday, while in the fields, the hardworking men and women must replenish their spent energies, so the women fetch the “home brew, thobwa.”

And in the evening, after the day’s hard work tilling the land, people entertain themselves to songs. The village playground becomes alive with melodious ‘songs of our people.’ Life, according to the song, is indeed beautiful.

But the more I listen to this song the more a feeling of unease creep in on me. Then the beautiful life that the song describes becomes distant, less believable.

All the beauty and happiness becomes cosmetic, made up, or better still, something wished for, but never to be attained in many of the villagers’ life time.

Eventually, it is the subtext that becomes louder and louder every time I listen to the song. I feel that ‘the life of an African’ that Lawi describes in the song is not the life for an African like me or Lawi himself.

Interestingly, it may not even the life of the villagers as the song claims. This reminds me of how artists world over have (mis)appropriated ‘ghetto discourse’. Ghetto is often ‘glorified’ by those living outside of it. Ghetto has often been popularised by those who do not live in the ghetto.

Either they escaped ghetto at a young age, or they have never lived there before and their only connection to ghetto is through imagination. This is actually very true with the romantic picture of village life in Malawian creative imagination and Lawi’s Life is Beautiful is one good example. One is tempted to ask: if life in the village is this beautiful, why do we have the problem of slams in the cities? Why are people flocking from villages to towns?

Cock crow and singing of the birds at dawn, which in the song heralds the dawn of another ‘happy’ day for the people in the village, may as well signal the beginning of yet another day of slavery for many of the village folk.

The smiles on their faces and the greetings could be genuine, but their supposed happiness is undercut by the fact that their day of toil has just begun.

It is possible that the majority of these people are actually not going to their own fields but to somebody’s farm to toil for a few grains of corn or some stale banknotes, stale in both looks and value. Thus, they hardly have time and energy to work their own fields.

When the voice in the song says: nthawi yokolola ikadza kumakhala chimwemwe [when harvest time comes, there is happiness], it only remains at the level of a dream for such people.

If I may sound a little Marxist, the fruits of their labour are not theirs to enjoy really, for such fruits are forfeited to capital at harvest time.

And from their own fields —usually planted with poor seed and largely left unattended— they can only manage a few cobs and a dozen stalks.

When such people sing at night in the village playground, is it really happiness that fills the air?

Do they really sing at all? Someone would say it’s just the children singing their innocent selves out, excited at the sight of the moon and of course, at the license to explore teenage desires and pleasures while their parents lie dead on mats awaiting another ‘bright’ day.

While in their fields of toil, the men and women, take time to enjoy some homemade thobwa. Thobwa is nice and thobwa is good but not when you have to drink it by default which I think is the case for many village folk. Given a chance, those people would not have thobwa for refreshment regardless of all the nutrition arguments we may raise.

Some actually cannot even afford a cup of thobwa in the village. Given a chance, they would want to enjoy a glass of ice cold juice or orange squash or anything like that—regardless of whatever argument we may put forward for tradition and its foods. And when these people sing at night, their so-called joyful singing would become suspect for me.

They may not be happy after all. Somehow when Lawi goes ‘helelehelelehelele mama’, I am haunted by undertones of lament. The song then ceases to be a song of happiness.

At the end of it all, I feel the way village life is presented in the song is dangerously simplistic, stereotypical at best, which bleaches an otherwise good song.

The age-old question in African (postcolonial) creative arts comes back to us: What is the role of the African creative artist and how must such a role be fulfilled? To tell the people where the rain begun beating them, Achebe would say.

Others would say, to show them that their life is not just one long night of darkness; yet others would contend: to tell the world that Africa is not just about hunger, disease, poverty and war, but that we laugh in Africa, we love in Africa, we ‘live’ in Africa, that we are alive.

For me, any art work that overdoes one of these elements runs the risk of inviting uncanny subtexts, which then begin to mock the work’s authenticity from within.

Do you have an issue with Lawi’s music or Lawi himself. Mwasowa zolemba eti?

Angry Patriot: I think you lack understanding this article. I personally think it is an academic piece of work and a critique as it were. It is more fitting for tose exposed to critical arts koma munthu wamba probably ngati iweyo Angry patriot need a bit of schooling to get to the gist of it.

You caught me out there Wailing Soul. Regardless, I still think the author let his mind wonder too far in his critique of Lawi and his art. It could be Lawi’s music is just so addictive the writer got caught in his Wizard of Oz imagination. Who said Malawi folklore is boring. This is just Lawi in his artistic wizardly reminding Malawi of her roots through song and dance. To quote and paraphrase; Lawi is saying “Malawi is not just about hunger, disease, poverty and dirty politics, but that we laugh in Malawi, we love in Malawi, we ‘live’ in Malawi, that we are alive”. Thank you Wailing Soul; I feel something waking up inside me; must be that glass of thobwa.

I think it is an art-critique only that Emmanuel Ngwira lacked balance in his writing.He has chosen to be pessimistic about the piece of the art. deliberately, he has not tried to reflect the intention of the song and climax part of the art in celebrating the beauty of village life. You will agree with me that even rich people who Ngwira would have loved if they shared juice with village people they sometimes miss village life. Some people like us who are well to do and are in town we sometimes miss our villages. We miss dancing to Manganje, Nkolowa that my grandmother cooks than nobody else, and of course Thobwa. These things do not remind me of my pooor background but rather the beauty, the richness, the hospitality and self glory of my village. There have been people who have tied development to beauty of life like Ngwira andWailing soul. It very difficult for such people to remember or occasionally visit their villages as it remind them their poverty and nothing beautiful their villages possesses. But those who have traveled in well developed countries will always miss the aroma that their cultural fabric feeds its people. I always ask why do people like Mutharikas, Goodall Gondwes, Chakwera, Mathews Mtumbukas e.t.c despite spending a good number of years working abroad they chose to still come back home where there is hunger, poverty and evil? I suppose there is still that one misses home connected to our soul which is culture… the dances, the muic, the language, the type food e.t.c. If you do not cherish them and Lawi’s mastery then define art appreciation?