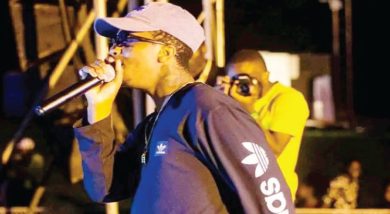

Legend: Matafale the fiery legend

The year was 1978. The place Chinkango Seventh Day Adventist Church in Chileka. The church was packed to capacity that Saturday morning.

One of the choirs performing that morning had a nine-year old boy who was upfront for the first time in a choir.

Everybody knew the boy’s half-brother Davis Kapito, who later in life, was to become a vocal politician for the United Democratic Front (UDF).

Kapito was well-known in the church, being a member of the beloved Christ in Song Quartet. He had incorporated his brother in the choir.

Overwhelmed by the curious eyes raining from the congregation, the boy was so nervous he started crying and thus, could not sing.

Fast-forward to December 31 2001. State-broadcaster Malawi Broadcasting Corporation (MBC) was announcing names of winners in the annual Entertainers of the Year Awards.

When it came to Musician of the Year category, many people in the Njamba Room and even those glued to their radio and television sets to follow the proceedings agreed on one thing: Evison Matafale was the man.

His song, Yang’ana Nkhope, off his second album Kuimba 2, was voted the second best song. The award came posthumous, as Matafale had died at around 3am on November 27 at Kamuzu Central Hospital, while in police custody.

The musician, whose popularity was sky-rocketing, was arrested on November 24 and was awaiting criminal libel charges for allegedly authoring a document that attacked, among others, the then president Bakili Muluzi.

And in January 2002, Nation Publications Limited (NPL) announced its Man of the Year Award for 2001. It was Matafale, who became the second musician to win the accolade after Lucius Banda had won it in 1998.

It is worth noting that Malawians voted for Matafale to win the two accolades a few months before his death.

Matafale’s mark in Malawi music is indelible. Two albums, with close to 20 songs to his credit and the tongues were wagging. He is Malawi’s reggae king, some said. Others said he was the one to put Malawi on the international music map, others affirmed.

He is a Toshite (a musical reincarnation of Jamaican reggae artist Peter Tosh). Others likened him to other Jamaican legends such as Culture’s Joseph Hills and Coco Tea.

Not without cause. His first album, Kuimba 1, which he released shortly after his return from Zimbabwe as a member of the Wailing Brothers Band, made many rethink their impressions of Malawi music. The hit song, Watsetsereka was on everyone’s lips. The other songs in that album, Chauta Wamphamvu, International Music, Malawi, Nkhawa Biii!, Wolakwa Ndani and Poison So Sweet remain tunes so deep and so sensible.

Shortly after ditching Wailing Brothers, Matafale formed his own band, the Black Missionaries with whom he dropped his second album, Kuimba 2 in August 2001. The album proved Matafale was no ordinary musician; it proved Matafale was here to stay, that he was no fluke.

The album brought songs such as Wolenga Dzuwa, Freedom, Mkango wa Ayuda, Sing a Song of Freedom, Timba, Umafuna Zambiri, We are Chosen, Yang’ana Nkhope and Zaka Zonsezi.

In fact, while that album was still hot, terrorists attacked American symbols of political and economic prowess: The World Trade Centre and the Pentagon on September 11 2001.

Shortly after, Matafale released Time Mark, in which he felt the attack were a fulfillment of the destruction of a kingdom as prophesied by Daniel: a kingdom symbolised by a giant made of several metals, whose feet were a combination of iron and clay.

After that release, some Americans were tracing him, looking for his signature.

In a nutshell, Matafale’s music was about unity and love: love for God and fellow man. He brought music for reflection, music for joy. Simply, it was music for the body (danceable), mind (for meditation and reflection) and soul (spiritual).

The little chorister had in 32 years transformed into a piercing artist on the brink of international repute. All that nibed in the bud with his death in police custody seven days after he celebrated his birthday.

Matafale, who had spent two years in destitution in Zimbabwe where he worked on some tobacco farms as a casual labourer in spite of his being a trained teacher, was known to be unrelenting in his fight against oppression. Even in radio interviews, especially with the then FM 101 presenter Patrick Kamkwatira, Matafale was fiery.

“I don’t dish out my music like I am giving porridge to a baby. Get the message behind it. If you don’t, you will perish,” he said in one interview.

That came hot on the heels of Matafale’s lambasting the Musicians Association of Malawi and Copyright Society of Malawi (Cosoma) for failing musicians.

“In Malawi music is a crime,” he said in an interview with The Nation after the OG Issa saga. “All musicians are criminals because they are fighting evil, which some people defend. Because I am a criminal, my future is doomed. I don’t fear death because my Bible tells me not to be afraid of those who kill only the body and not the soul as well.”

About four months later, Matafale authored the letter that attacked certain politicians, religious leaders and businessmen for their evil deeds. He was sought by police for that document.

On November 24, police arrested Matafale at his Chileka home. He was ailing then, and they told him he was only being taken to the station for questioning. Yet, he was taken to Chichiri Prison, then all the way to Maula Prison in Lilongwe where his condition deteriorated before he was taken to Kamuzu Central Hospital where he died three days later.

Today, 14 years down the line, some of those close to Matafale feel the musician is not resting in peace since police officers who mistreated him to death did not face the law. One of them, Matafale’s close friend and confidant, Lawrence Chakakala Chaziya, believes injustice reigns.

“He was not just a musician. He took time to compose songs and sought counsel before the songs went public. He sought to unite all people with music. If he were to come to life again, he would find that injustice is just as deep-rooted as it was the time he died fighting. Those who slay him were left scot-free,” said Chaziya.

Was he not on South African Gradiators?