Making zero hunger campaign reality

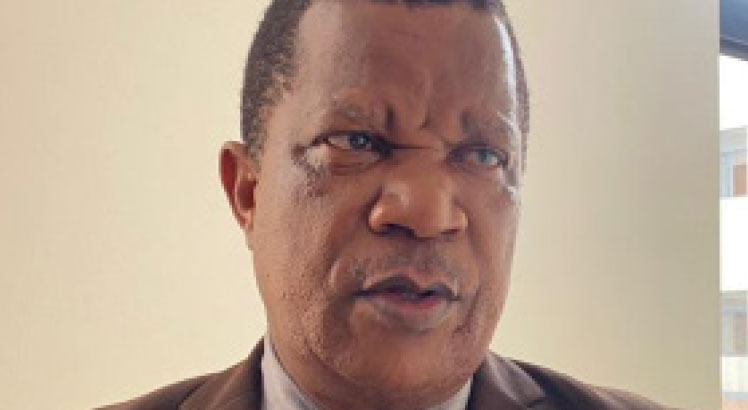

In 2015, the global community adopted the 17 Global Goals for Sustainable Development to improve people’s lives by 2030. Goal number 2 pledges to end hunger, achieve food security, improve nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture by 2030. Zero hunger campaign is the core mandate of World Food Programme (WFP). In this interview, our staff writer BOBBY KABANGO talks to United Nations WFP country representative, Benoit Thiry.

You are talking of a zero-hunger world by 2030. Do you see Malawi achieving this goal come 2030?

Yes, it is possible for Malawi to achieve zero-hunger by 2030. Achieving Zero Hunger is a shared responsibility. If all stakeholders come together and work in partnership to build a truly national movement, we can build sustainable agriculture and food and nutrition systems. WFP is working with the Government of Malawi and relevant stakeholders to address challenges that threaten the realization of this goal. To support this, WFP alongside other UN agencies, is supporting the Government of Malawi in conducting a nationwide Zero Hunger and Malnutrition Strategic Review, under the leadership of the former Vice President, Dr. Justin C. Malewezi to develop recommendations that can fast-track progress towards achieving SDG 2. WFP is also shifting its focus from cyclic humanitarian response to building resilience to break the cycle of hunger in support of achieving this goal. With the required combination of policies and leadership, ending hunger and undernutrition by 2030 is possible.

What is your office doing in making this dream become a reality?

WFP is supporting the government of Malawi to create a food and nutrition secure and resilient future through implementation of social safety net programmes linked to sustainable long-term resilience building. For WFP, having an integrated approach to address food insecurity in a context of a changing climate is key. Being rolled out since 2014, this integrated approach to resilience building is already demonstrating good results, and has the capacity to be scaled up for the benefit of other households facing food insecurity. We are also working closely with the government and partners to build and leverage national systems in response to food insecurity, and ensuring linkages across the humanitarian-development nexus to support households moving away from cyclical crises and onto a sustainable graduation pathway.

But my point is to understand what is your office doing on the ground to achieve this dream?

On a practical level, we are providing daily school meals to about one million primary and pre-primary students; nutrition support to 337 000 people with acute malnutrition and support to building resilience among communities and households by creating assets for 132 000 households. We are also supporting 34 000 smallholder farmers to reduce post-harvest losses and linking them to markets so they can sell their produce at a better price.

I understand that you’re encouraging irrigation farming in some parts of the country like in Lirangwe, Blantyre. This is coming in when Malawi is experiencing droughts in most parts of the country. Do you see this initiative working? Or what mechanism have you put in place to register successes in the irrigation sector?

We are aware of the droughts, but what we are doing is to support communities to build productive assets using a watershed management approach, which will support the replenishing of the water table for the benefit of healthier ecosystems that can be used in turn for productivity gains. We are also supporting 10 solar powered micro-irrigation schemes in the districts of Nsanje, Zomba, Mangochi, Karonga, Chikwawa and Blantyre which are targeting vulnerable and food insecure communities and households. The schemes promote diversification of crops and aim to change farmers’ practice of growing maize every year but to produce high value and easily marketable horticultural crops. The pilot schemes have demonstrated very good results by increasing yield substantially and restoring the water table. Such success stories have the potential to be scaled up by the government with the support of WFP.

You have just told me of the home-grown school meals programme which your office is implementing in Phalombe. How many schools are benefiting from this? Do you see it also contributing to the zero-hunger goal?

The Home-Grown School Meals (HGSM) is a model of WFP’s school feeding programme that sources locally produced food for learners and helps increase knowledge about the use of locally available food and boost local economies. The model empowers schools to be independent in managing their own funds for successful decentralization, creating awareness in communities about the importance of providing nutritious food to students and applying lessons learned in their homes. This model is in line with the government of Malawi and the African Union’s HGSM policies and is capable of being scaled up in Malawi to advance educational and food security outcomes. WFP provides funds to schools through the district councils, to purchase food locally from farmers. In 2017 alone, a total of 89 primary schools were reached across four districts of Phalombe, Salima, Mangochi and Dedza and 107 000 primary school students are currently benefitting from the HGSF programme. Participating local farmers now have access to markets thereby increasing their incomes and capacities. In Phalombe, WFP supports five schools under this programme benefitting over 8 000 learners.