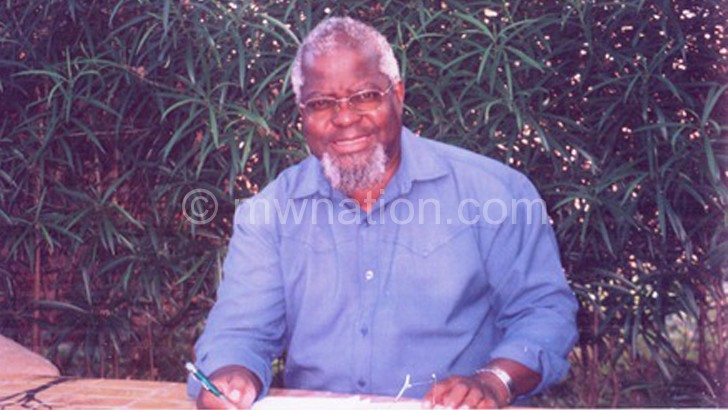

One-on-one with late Professor Steve Chimombo in 2009

Correspondent Kandani Ngwira interviewing late Professor Steve Chimombo in 2009.

As a pretender in the writing business, I have always been awed by your diversity of genres and variety of topics that you write. I have always thought you deserve a special place in the academia and in the writers’ circles. I shall, therefore, be content in whatever small measure of recognition that this article would bring to Malawi’s foremost writer, Professor Steve Chimombo.

Once gain Happy New Year.

- What is your full name? It occurred to me when Moira was giving me the email address that you have some middle names that I did not know despite being your student at Chancellor College. I thought our readers might also be interested to know.

Steve Bernard Miles Chimombo.

Bernard is my father’s name

Miles was his father’s name

Chimombo is the family name, which I trace back to Msinja—you can check on it.

Nkhoma is the clan name, but I don’t use it often.

- When were you born and where do you hail from? Is there anything particular about your up-bringing that may have influenced your life to be what it is today?

I was born in 1945. My father was a meteorologist, so he knew and told me about Napolo, which passed our village about ¼ mile away. He encouraged me to read and write a lot. He had books, he would buy or get me books, or get me membership to the town library in my primary school days.

My mother was another great influence on me. I remember the nights spent telling stories, singing native and Christian songs, or reading, including the Bible, or dancing and acting sketches.

I had some friends who had access to reading materials outside our family at Chileka. I utilized their friendship, including the bookseller at the airport kiosk.

I used to walk 30 miles to and from Chileka and Blantyre to buy second-hand books from the LTC shop.

I liked acting a lot. I used to recite my favourite poems at school shows in primary school

My father gave me some scrap paper with which I constructed notebooks. In these I used to write imaginary and true stories I had heard, and even poems and jokes I liked from other books.

I grew up with all this.

- Take us through your academic career. How did you start and where did you go to up to your professorship?

We were the ones who opened the University of Malawi in 1965. I remember coming straight from secondary school and sitting together with older students who had gone for a year or so already at the then University of Livingstonia. I got a first class degree at the end of four years, taught for a year at Soche Hill Secondary School, and went to Britain to take a Diploma in Teaching of English as a Foreign Language in Cardiff, in Wales; then a Masters in English Literature at Leeds University. I came back in 1972 to join the University of Malawi as a staff member. I taught for four years before going to the United States.

Teachers College, Columbia University, did not trust the degrees anyone got outside that institution, so I had to do another Masters, then a Master of Education before I was allowed to do a doctorate. My degree is actually Doctor of Education, not Doctor of Philosophy as most people expect.

Add to this an Honorary Fellowship in Writing I got from Iowa University International Writing Program, I have seven degrees really. I didn’t want to boast about them when Kamuzu Banda was alive, because the regime was sensitive to how many degrees other people had. I’d have ended up being food for crocodiles.

- How long have you served in the university system. Why did you quit at a time when the country is complaining of brain-drain. Surely the university could have been privileged to use a knowledge storeroom like yourself. I have in mind the young students who could have learned one or two tricks on how to make the pen dance on paper.

I was with the University of Malawi from 1972 to 2002, when I retired. After serving for 30 years without defecting, I felt it proper to pursue my writing career, since I was in danger of being swallowed up by the system. I was Head of Department for two sessions, in danger of being made Dean or Principal, or something equally bad. I felt my writing was more important than an academic career by this time. The university has no room for writing professors, so I decided to continue writing at home.

- Let’s come to your writing career. How did you start, what inspired you?

I started writing in primary school. My father gave me a lot of scrap paper which I pinned together to form notebooks. I wrote my stories, stories I had heard from my friends, even poems and other things I liked from the books I read.

Some of the stories got me a shared first prize in creative writing in Form 3. One of them got me internationally published in Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) at the end of secondary school.

[For my sources of inspiration see 8.]

- You are among the original first known writers in Malawi from the Writers Workshop. Tell us what it was like being a writer in the 1980s when the environment was oppressive with the draconian rules imposed by the censorship board. How did you survive? What was one of the most touching experience you went through during that period that you would like to share with us?

I was a published writer before I started college. I was on the first Publications Committee from 1965. The Censorship Board was fully established around 1966. It then became a game of who would win. When I joined the university as lecturer, my head of department and a staff member, both expatriates, didn’t win, and were repatriated because of Odi, our creative writing magazine. I used to edit Outlook for the department, so I have first-hand experience of the Censors. They demanded to read articles before the magazine was published. I published one issue before they had seen it and I was required to submit all the issues to the Vice-Chancellor. That was its end.

My personal experiences with the Censors are many but I’ll mention one : the Napolo Poems. I published some of the poems in Odi, others in Outlook, yet others outside the country. When I wanted to put them into book form together, the Censors would not allow it. I explained to the Secretary of the Board that all the poems had already been approved, except for one—“A death song.” Only then was I allowed to publish the volume, without that one, of course.

- You write short stories, poems, novels, plays, monographs, books, book reviews, literary criticism, WASI etc. Among these genres which one do you enjoy most, that could be said to be your favourite?

This is a difficult question for a writer who writes in all the genres. For example, I’d start The Rainmaker, a play, and find that some material doesn’t fit the play, but works very well in a short story. So I’d publish that, but at the same time write an article on the problems of writing on that theme. Or I’m writing The Wrath of Napolo, find that part of it actually suits a long poem, so write The Vipya Poem. Or find that the novel has got several poems, and even straight travelogue articles, and I have to publish them all.

- Where do you get ideas to write all these things? What really inspires you?

As my writing demonstrates, almost anything inspires me. I look at Zomba Mountain, out comes Napolo Poems. I jump on a ship, out comes The Wrath of Napolo. I drive along the highway, and the poem, “The Politics of Potholes,” come out. Its been like that throughout.

- Which of your pieces of writing do you like most? Which one do you go home, pick from the shelf and read?

This is related to 7—same answer.

- Apart from yourself, do you admire any other writers? if so who and why?

I really admire a small selection of writers:

T.S. Eliot: His collected poems are on the shelf in my study. He is brilliant, especially his “Wasteland” and “The Lovesong of Alfred J Prufrock.”

Joseph Conrad: He was my special author, in the last year of my undergraduate days. His Heart of Darkness is on the shelf in my study.

Wole Soyinka: Both his poetry—for its epic dimensions—and plays—for their themes and execution. Especially “Idanre” and “The Lion and the Jewel.”

Shakespeare’s Macbeth: I studied Macbeth in my last year of secondary school. He is the only English author I’ve written more than three published articles on. The whole play is inspiring for an African who grew up in a witch-ridden society.

I studied all the above in my last two years as an undergraduate and a secondary school student, but they have all stuck in me.

- If you had not become a writer (which could never have happened because I feel you were born with a pen in your hand) what could you have been? What is it that you love to do aside writing?

If I had not been a writer, I’d have become a journalist. In fact, I wanted to become one, only there wasn’t a course on offer in the university. I took it in the end, just to teach journalism and be accepted as a journalist.

I know it’s close to writing, but I can’t see any other profession! Perhaps an actor, on stage or in film.

Apart from writing, I read.

I like karate, for sport and relaxation. I’ve discovered I’m even writing on it for a magazine.

- Napolo is an overriding metaphor in your poems. Tell us what about it or what attachment does it have to you that it came to influence much of your writing?

Napolo is many things to me. It is the creature that lives under the mountain or lake. I read about its exploits on Zomba, Ulumba and Ntonya mountains in Zomba, or Mulanje. I hear it passed ¼ miles from my village in Zomba. I wrote about it. I was on the MV Vipya on the lake and it sank the ship on its next trip. I wrote about it too. It is somehow related to me—that’s why I dedicated the poems to my son of that name. I’m still trying to unravel what it means to me.

- You wrote a long poem on MV Vipya which drowned some time back. Is there some personal attachment to that too?

I was on the Vipya on its last-but-one trip. See 12.

- I have loved to read your book reviews because they are rich with information. What can you say about writing in Malawi to? Am referring to quality, direction and perhaps the way forward?

Writing in Malawi is an inexhaustible subject. Even when it doesn’t exist, you still can write on it.

Quality: Only a few novels and poems would pass my strident tests. As for plays, none is writing them these days, so the least said is the best for them.

Direction: You can’t have it when there’s nobody to take you there.

The Way Forward: If there was any to take the plunge, a teacher would surely be found.

- You have been writing WASI on your own. For how long has WASI existed? Who is the audience and what is the focus. How do you manage to write on your own?

WASI was not always written on my own. The first and last few issues, maybe. In between there have been numerous contributors, Malawians and non-Malawians, too. It started 1989 but was first published in 1990. The audience maybe changing, too, but it has always been the artist. At first it was the writer only, then all artists, now we’re in between. The focus is always the artist and his work. I may have strayed into tourism, because no one was going into it, but the major thrust was never lost sight of.

- I remember in my college days, you never liked computers. You always loved writing raw with pen on a piece of paper. Did you write all your books that way? Do you still avoid computers?

I never like machinery to work on my writing, but over the years I’m learning to make it work for me. But I still compose long-hand and type the results afterwards, including The Wrath of Napolo, all six hundred pages of it.

- Writers are known to lead an eccentric life style. You used to keep long hair just as many writers like Wole Soyinka what about it, I the Afro hairstyle and writers. They say the long hair gives a writer a sense of freedom, is that so with you?

I loved my long thick hair, which I kept without cutting, without any ointment even. I guess that’s why I lost it. But when young, I used to cut the hairline to look more like my father. Now I look more like him, hairwise. Both had nothing to do with writing!

- You also used to be a chain smoker. How did you manage to break the habit?

In the 1980s I went through some serious unknown sickness and I wanted to break away from any negative practices that might bring it back. I went “cold turkey” as they say in English, in other words, I stopped from one day to the next.

- You have written some stories in your vernacular Yao. Is this in line with Ngugi’s language debate?

I am Nyanja/Mang’anja actually, living perhaps in Yaoland. I haven’t written any fiction in my language, only prose, explaining some of the Napolo ideas, and one play, Wachiona Ndani? It was a native Yao speaker who translated the play into Yao.

- Any major book project that you are working on at the moment?

I’m always working on several book projects, some are actually finished, but don’t have publishers. The biggest, which I started piecemeal in WASI is a complete relook at Malawaian Literature. The smallest project is putting together my short stories into one book form. It hasn’t been done yet.

- All your children have Chichewa names full of meaning. I would love if you mention their names. How is this when you are married to a white wife?

a-Tina Dhana, 1st born. Tina from Ike and Tina Turner, actually! Shortened also from Christina, my younger sister. Dhana is from Hindu, meaning cheerful forbearance.

b-Christopher Zangaphee, 2nd born. Christopher from the carrier of Christ. Zangaphee was my attempt to be left alone. It’s from my childhood.

c-Napolo Alexander, third and last born. Alexander is the greatest, really! Napolo is from the subterranean and submarine being. It passed ¼ miles from my father’s village.

So now you know.