Osiyana 2 years after floods

The way locals pause and shake their heads when recounting the horrors of 2015 floods says it all.

Most of them have never seen a worse disaster than the floods which killed 176 people in the Shire Valley and surrounding districts two years ago.

“If the area had no trees, most of us would have been swept to the grave on January 13 2015 when floods reduced homes to rubble,” says Paul Mailosi.

He survived the floods which displaced 200 000 people in Nsanje.

Osiyana villagers in Traditional Authority (T/A) Mlolo in Nsanje spent up to four days hanging in trees before Malawi Defence Force (MDF) dispatched helicopters and rescue teams to the swamped areas.

Geographically, the low-lying rural population near the confluence of Ruo and Shire rivers is vulnerable to floods that often wreck homes, livelihoods and wealth.

For years, the two rivers have been getting shallow—buried in silt emanating from hugely deforested highlands on their banks.

The worst tragedy struck when unyielding downpours in January 2015 culminated in a devastated flood that compelled President Peter Mutharika to call for external intervention.

The majority of the dead were Osiyana villagers.

The survivors witnessed the raging floods sweep livestock and their neighbours, friends and relatives.

Those who clang to tree branches in the middle of ruthless floods say it was survival of the luckiest.

Mailosi, whose family of six was saved by an Acacia tree, says many others fell from trees and got washed away.

“By the fourth day, they were too hungry and frail to hold firmly to the weakening branches,” he says.

From “the tree of life”, he watched the water levels rise until his home submerged and crumbled.

“If it was not for trees, we could all have gone,” recalls Mailosi.

The disaster shattered livelihoods of the poor, deepening hunger and poverty.

“From the tree, I saw my five cows, 15 chickens and 34 goats gasping to breathe as floods swept past the tree, taking them to the Shire which had also swelled beyond its banks. The sight still haunts me. The cows were my family’s prized asset.”

When the rescue team arrived four days later, his family was airlifted to Bangula Camp where they spent two months.

From the helicopter, they saw canoes evacuating others to a hilly side of Osiyana.

After two months of relying on relief items, some survivors of the humanitarian crisis did not return to the ruined villages.

They relocated to a new place in the hills where they had to start all over again.

“With everything swept away, it has been hard for us to rebuild our lives,” he says.

According to group village head (GVH)Osiyana, crop fields of farmers, who rent plots in fertile wetlands along the Ruo, were ravaged by drought, fall armyworms and locusts.

“Our fertile land was buried in sand. The new site in the hills comprises barren soils and farmers cannot thrive in this setting. Although some organisation assist with food, life is hard. We used to have food before the floods,” says the traditional leader.

About 664 households have relocated from 30 villages under GVH Osiyana to the hills, but only 53 occupy decent houses. Some of these homes were constructed by Malawi Red Cross Society, a humanitarian organisation which works to lessen the suffering of people in emergency situations.

The rest of households dwell in mud shacks.

Government has drilled 11 boreholes—increasing the number of water points in the settlement to 20.

But Osiyana residents appeal for more boreholes for the growing population.

“We spend almost three hours to get a bucket of water. The environment is unhygienic and lives are at risk of water-borne diseases,” says Mervis Boloma.

The struggles for water dissuade some households from leaving the flood-prone “as no one wants to move where there is no water” says the woman.

“The future looks bleak as the ‘new’ home has no basic amenities,” explains Village Civil Protection Committee chairperson Ishmael Mackson.

He wants government to construct a clinic closer to the settlement to ensure no one dies of treatable conditions.

“Besides the absence of a clinic, there is no school. Some children have dropped out of school due to long distances,” he explains.

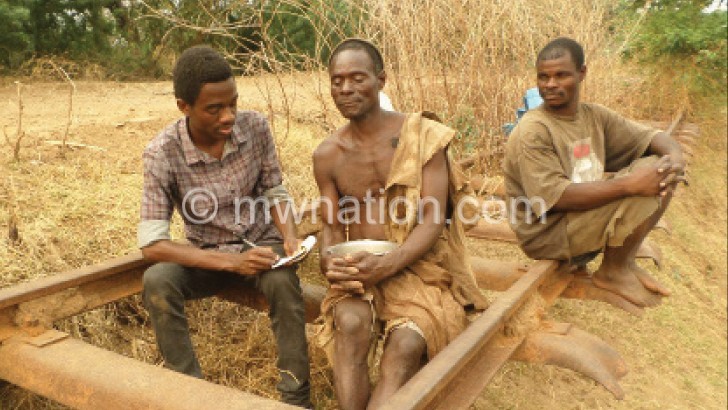

Another villager, Balton Damisoni, says most of their incomes come from public works under Local Development Fund (LDF) and charcoal burning.

“Things got worse when most NGOs suspended their aid. Only Care Malawi provides each home with 15 kg of beans and four litres of cooking oil every two months. This is not enough. This is why many are resorting to charcoal making,” he says.

As charcoal business grows, the trees are vanishing at an alarming rate, much faster than forests are being replenished.

To GVH Osiyana, this points to a repeat of the 2015 tragedy which forced the Ruo to change its course—leaving Makhanga Market cut off from the rest of the country.

Now reduced to a ghost trading centre, Osiyana has become an island only reachable using canoes. n