Pangs of ‘free’ primary education

When government adopted the Free Primary Education Policy in 1994, Paul Rashid was a 17-year-old student who assumed, in truth, the much-touted free primary school meant ‘free of any charge’.

Yet, 24 years down the line, the 41-year-old widower

These costs include development fund and examination fee. There is also administration fund, which covers security guards and cleaners’ fee, water fee and school report production fee.

The charges that schools set range from K300 to K7 000 per pupil per term or per year, depending on the school’s locality, which most parents, especially in rural areas, cannot afford to realise.

However, the forcing of learners to pay funds is in conflict with the Free Primary Education Policy, which stipulates that no learner shall, directly or indirectly, pay for basic education and does not make payment of other funds mandatory.

Rashid is now a frustrated and bitter person with chants of ‘free primary school education’ because his youngest son, Chifundo, dropped out of school after failing to pay a K300 development fund.

The man from Patasoni Village, Senior Chief Symon’s area in Neno, used to operate kabaza (bicycle taxi) at Zalewa Turn-Off Trading Centre in the district, until early this year when he fell ill and could hardly raise money for his family, let alone his son’s school fund.

He was diagnosed with tuberculosis (TB) in March this year and was advised by doctors to break off from his energy-demanding business.

Chifundo, now 14 years old, spends his time at Zalewa Turn-Off doing casual work. Among others, he sells fresh roasted maize, mostly to motorists and travellers along the busy M1 Road. He dropped out of school while in Standard 7 at Malizakamba Primary School.

“His life has now transformed into more of a ruffian because I no longer have the strength to control him,” Rashid narrated to Nation on Sunday crew that visited him at his village Thursday evening.

The situation, he explained, worsened after the death of Chifundo’s mother in October 2018, as she used to help in paying the development fund.

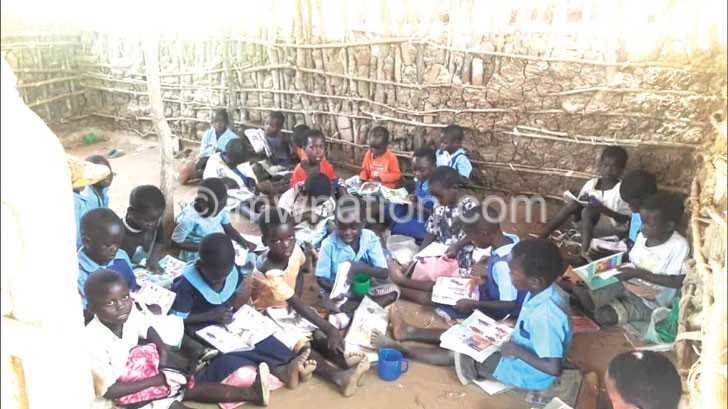

Chifundo’s predicament is not exceptional. Studies show many pupils are failing to access free education as they are constantly denied the opportunity to attend classes or write examinations for failing to pay the invisible fees.

Some learners, as young as six, are forced into child labour to help their parents raise money to pay the funds at school.

For instance, exclusive of Chifundo, Nation on Sunday also found a number of young boys and girls at Zalewa and Thabwa roadblocks in Neno and Chikwawa districts respectively, engaged in child labour to raise money to pay at their respective schools.

The learners claimed they were released from classes after their parents failed to raise the development fund and had no choice but to engage in casual labour.

At Thabwa roadblock, some pupils from Thabwa Primary School walk up the nearby hill to fetch firewood to sell to chips and kanyenya (roasted or barbeque meat) vendors while at Zalewa, the learners from Zundu Primary School are also engaged in assorted trade.

In Balaka, Elizabeth Divasoni, whose child is at Mponda Primary School, said her son missed classes for two weeks after he was told not to attend for not paying K400 as development fund.

“I fell sick and as a single parent, I failed to raise the K400 because I could not manage piece works that bring food and other basic necessities in my house. I am certain he missed a lot although I am yet to see his results,” she told Nation on Sunday.

The United Democratic Front (UDF) administration adopted the Free Primary Education Policy in 1994 to ensure that every child attends primary school and barely after a year, enrolment tripled from 1.6 million to over three million.

Although some educationists argued at the time of introduction that the system was not workable, four different governments have insisted on implementing it.

When contacted on the matter, principal secretary for Ministry of Education, Science and Technology Justin Saidi referred Nation on Sunday to ministry’s spokesperson Lindiwe Chide, who was not available.

While describing the development as unfortunate, Neno district education manager (DEM) Reuben Menyere said they discussed with head teachers, school management committees (SMC) and primary education advisers (PEAs) to channel to his office all challenges for redress.

“Otherwise, this is unfortunate. We have other stakeholders like the social welfare department who can come in. For instance, that school [Malizakamba] is under World Vision International, we could have found ways of assisting the learner to deal with his challenge,” said Menyere.

Chairperson of Parliamentary Committee on Education Elias Chakwera feels ‘it is a mockery’ to parents and guardians because they are subjected to indirect school fees.

“We cannot be telling poor parents in the villages about free primary education. We tell them one thing and demand another. To me, it only shows we are a nation with no direction,” said Chakwera.

He added: “What is happening is against what the framers of the Free Primary Education Policy had in mind.”

But social and governance commentator Martin Chiphwanya said the idea to set up free primary education was in the right direction in attaining education for all, except that the policy was hurriedly implemented, without sufficiently considering the issue of resources.

“There has been high influx of pupils over the years, a thing that has comprised quality, and standards have completely gone down,” said Chiphwanya.

He suggests that to address the issue of resource pressure in implementing free primary education, there is need for private sector support and communities’ lead in mobilising resources.

But Neno South legislator, Mary Khembo, said government needed to consider a special policy that would allow the “very less privileged” learners to be exempted from paying development funds and other expenses.

“There is also need for the private sector to balance up. For instance, in my constituency more NGOs come to help girl pupils than boys,” she said.

Last year, the Mzimba Education Network (Mziden) conducted a survey which revealed that primary education in the district was not free as teachers and school management were setting up norms that force learners to pay money to finance certain school activities.

The survey revealed that learners were paying K2 000 each for development fund, water bills to access private water points, administration fees and K150 for examination report card processing, totalling K6 150 per term.

The study came after the Civil Society Education Coalition(CSEC) also conducted another one on hidden costs of free education,