Ralph led a good life

“Iwe, Chaffer, wayamba ulesi eti! Why didn’t you write your column this week?” He chastised, adding, “readers have no idea whether you were out of the country or not, whether you were sick or not. All they know is that you promised them your thoughts every week, which they look forward to. By not writing this week, you broke that promise.”

That was Raphael Tenthani, the legendary journalist who wrote for The Sunday Times, British Broadcasting Corporation and several other respected international news outlets.

They were words that have left an indelible mark on me. Remember, this is the man who, while battling for his life at Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital in Blantyre after a nearly fatal car accident that also almost left him blind, used one hand (the other one was badly injured) and a partially blind eye, to write his column.

He never used his hospitalisation as an excuse for breaking his promise to his readers. And, like most of his writings, that entry from the depth of excruciating pain on his hospital bed, was a masterpiece — and flawless.

Weeks later, he rose from the ashes of that wreckage somewhere in Liwonde to clutch his pen even tighter and made it even mightier.

He used his second chance in life to further show that journalism was a promise never to be broken so casually; a sacred calling never to be desecrated and a patriotic embrace that should never be betrayed.

That was Ralph10, as we used to fondly call him sometimes. It was never about him, but about the reader to whom he fiercely believed he owed his fidelity.

And so he wrote, every week, to the powers that be with a specialist surgeon’s non-negotiable precision.

Week in, week out, he penned, with the courage of a man who knew his worth—priceless.

He wrote like the extraordinary thought leader that he was and always will be—even in death.

Yes, Ralph wrote, with the honesty and fairness of a man who knew he must gingerly balance between his own freedom of expression and the subject of his writings’ right to their personal dignity.

Every day, for the international media, he told the story of Malawi and Africa in general with the captivating powers of a very gifted man; with the objectivity of one who knew and accepted that he had the power to change the narrative, but responsible enough to know the dangers that lurk when such power and influence is used irresponsibly and recklessly.

As a person, Ralph never took himself too seriously. I am inclined to believe that he cared more about what people thought about his brain trust and professional conduct than his appearance.

And so when, on the rare occasions that he put on a necktie, we all enjoyed that moment of seeing the ‘working man’ in him. Otherwise he was comfortable in his favourite loose shirts and buggy shorts—some of which attracted a lot of social media chatter. It was part of his persona, of Ralph the brand.

This was a man who was always at peace with himself—never in a hurry. He could take one hour seeping—or was is brushing the liquid onto his lips—a glass of wine on a bar stool while reading classic books even as heaps of newspapers patiently awaited their turn.

His generous heart was something to behold. He always wanted to share so much that sometimes he would irritate some of his closest friends.

He would call, say at 1am, and ask: “Mulikuti wawa!” And I retorted irritably one day, “Ralph, I am where normal people are supposed to be at this hour—in bed!

He chuckled, “Come we drink iwe, I am buying!” I switched off my phone, turned towards my better half and left Ralph to his own devices.

And for a man who was a global journalism icon, his humility always amazed me. One Sunday he called me. “Iwe Chaffer, uli kuti?” I told him I was at the office. He asked me to find him at Blantyre Market.

I went there and could not locate him. I called Ralph to find out where he was. He gave me directions. Guess where I found the great Ralph? At a stinky opaque beer joint near Mudi River just below the ‘Bus Stands’.

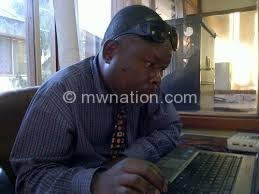

He was surrounded by obviously unkempt folks with whom he was sharing packets of his favourite beer—Chibuku—his laptop beside him. “I draw my inspiration from these people,” he told me after noting my questioning look.

It was this ability to be comfortable in both worlds—the polished life that hotel bars give you where he seeped his wine by night and the impoverished surroundings in taverns by day where he gulped his Chibuku—that gave Ralph the broad world view that helped him to analyse issues better than any local journalist I know.

One last lesson I learnt from Ralph10: You may be a respected professional, but there is a whole host of staff you don’t know. Always ask, even a cub reporter.

And so Ralph sometimes honoured many budding journalists by asking them to look at the great man’s copy, especially if he was tackling a subject he was not too sure about!

He knew which journalist was good at what and consulted them all, never underrating anyone.

No wonder every journalist, from a beginning reporter to a veteran, loved and respected him — not because of his star power and certainly not because of displays of material worth (he cared very little about that), but because Ralph was humane.

He led a good life.