Researchers at war with blue gum pests

Tucked in a colonial building at the foot of Zomba Mountain, State-sponsored scientists are edging closer to a novel breakthrough to ensure eucalyptus or blue gum forests are free from devastating pests. Our Features Editor JAMES CHAVULA writes.

Blantyre-Zomba Road is no longer the same. Forget the haunting flashbacks of a hugely battered tarmac—narrow, irredeemably potholed, with patch-upon-patch and jagged edges that pushed motorists to scramble for the fairly rugged space on the midline—that was being reconstructed when heavy machines were seen uprooting and chopping time-honoured trees four years ago.

Now, the fiery race to the white line has ceased. The tattered tar has been replaced by a new highway, wider, smoother and properly marked. Vehicles that used to stutter at a snail’s pace now cruise beyond the recommended speed limits.

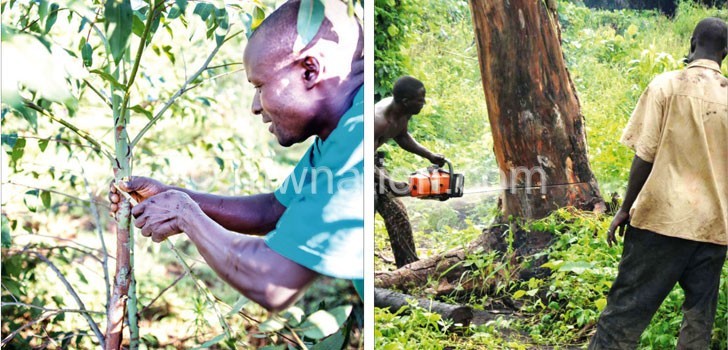

But this is not all that has changed on the 60-kilometre voyage. On the sidewalk, both indigenous and exotic trees are vanishing at an alarming rate, but it is unmistakable that eucalyptus forests are being silently annihilated by an outbreak of three pests traced back to Australia from where the widespread exotic tree originates.

As we speed off, the endangered trees flash past one by one. They are drying and dying. The remnants have to do with blackish or deformed leaves that eventually dry and die leaf by leaf.

The trees under attack are more pronounced at Thondwe where a thick forest once stood majestically. The spectacle of drying trees evokes memories of shocking encounters along Lake Malawi, with those travelling past the shoreline districts of Nkhata Bay, Nkhotakota, Salima and Mangochi being bombarded with the worst hit eucalyptus forests where dry trees come into view.

At Chintheche in Nkhata Bay, forestry patrolperson Mafuleka Jonazi lamented: “The forests are being wiped out by the pests. In my area, scores of farmers have cut down the blue gum trees because they were misinformed that the sap dripping from affected trees are poisonous. They wanted to kill the trees before they were killed.”

In the area, it took just a rumour and a few axes to send trees almost 10-years-old crashing to the ground. Now, researchers say the honeydew falling from affected trees does not kill unless it is contaminated by lethal substances. The stumps are sprouting again, but the pests are not relenting.

“Until the pests are finally eliminated, Malawians will continue crying for the lost trees, which are vital when it comes to firewood, poles for construction and timber,” says Jonazi.

To them, there is nothing to smile about the tragic situation on the roadside.

It is no secret that the country is losing its forest cover at the worst alarming rate in Southern Africa, but a consensus is gaining sway that something needs to be done to control or tackle the pests before they wipe out half the endangered trees.

A grim future

The three pests under investigation—bronze bug, gall wasp and lerp psyllid—have reportedly left half of the country’s exotic forests at the risk of systemic extinction.

At worst, those fearing “the unknown” are chopping and uprooting eucalyptus trees to keep the pests in check.

To many Malawians, this is the burning issue: What lies ahead for the remaining forests?

We put this question to plant and pest scientist Gerald Meke in Zomba.

“The future of manmade forests does not look good,” he says. “The three invasive pests that are attacking eucalyptus will have a great impact on deforestation.”

Alternatively known as blue gum, eucalyptus trees grow fast and meet the needs of most Malawians searching for fuel wood and poles as natural forests disappear faster than they are being replanted.

For almost four decades, government has been encouraging Malawians to plant eucalyptus to meet these needs and the uptake has been overwhelming.

“Estate owners and government plantation managers have planted over 60 000 hectares of eucalyptus as plantation trees. This estimate leaves out individual trees planted by villagers,” says Meke as we drive past colonial buildings that pave a mazy street in the shadow of Zomba Mountain.

At the foot of the second tallest mountain in the country, we turn left. At the end of Kufa Avenue—named after largely unsung hero John Grey Kufa who starred in John Chilembwe’s pioneering nationalist uprising in 1915—is a wire fence circling colonial buildings with algae-laden foundations, enduring walls and green roofs.

This architecture tells tales of times, immortalising a legacy of British colonial governors who made the eastern city their seat of their rule.

But the buildings in a setting of a derelict Parliament building long abandoned is not just another monument of a raging battle between modernity and history that plays out in the old seat of government.

It encompasses Forestry Research Institute of Malawi (Frim), where studies have been going on since 2008 and scientists are silently plotting the warpath to end the devastating pests.

As we enter his office, Meke tells me: “If the pest is not controlled for the next two to three years, most of the current standing trees will die and they will become a fire hazard. The country will run out of fuel wood and poles.”

In his reasoning, he sees total destruction of eucalyptus—almost half of the country’s exotic trees—pushing people to turn to the remaining indigenous trees in a desperate search for poles as well as firewood for kitchen use and for culling tobacco.

To him, saving the surviving eucalyptus is a necessary war. It must be fought fast and it must be won. The weapons are all over his office: the maps and charts on the walls, the fact-sheets and posters on every table, the stacks of papers and files containing findings trickling in; and the bottles of chemicals both tested and untried.

The attackers are ravaging a no less tree, he says. He says the widely grown trees are more or less like what maize is to the agriculture.

He explains: “Any serious attack on maize is doom for the country’s food security. The current pest outbreak on eucalyptus is an attack on pole and fuel wood security directly.”

At Chimpeni Tobacco Estate, less than 10 kilometres from Zomba Military Air Wing where the first incidence of lerp psyllid was discovered last year, appeals for an urgent solution to the pests which have already killed thousands of trees.

Breakthroughs

But not all is lost as the researchers say introduction of creatures that specifically feed on the notorious pests has the propensity to save the trees at risk. They call this path “biological control”.

“There is hope,” Meke assures me. “The ground-breaking strides are that we have identified natural enemies that we can use to control the pests. Between 1986 and 1998, we were able to control aphids attack on pines, mkungudza and Mulanje cedar on using a similar strategy.”

On the mission to save eucalyptus, four Malawian researchers are collaborating with three South African counterpart based at the University of Pretoria as well as two in Kenya, one in Zimbabwe and another in Uganda.

The team has identified the harmless foes in focus that prey on bronze bugs, lerp psyllid and gall wasp.

In their minds, they envisage the natural enemies, to be imported from South Africa this month, mauling the menacing pests until eucalyptus forests are free to thrive.

This path is not unprecedented. It was tried when Mulanje cedar was under attack ago and it proved effective in saving the worldly acclaimed hardwood exclusive to Mount Mulanje, the tallest in the country.

“This will work as a permanent solution to the pest problem,” he says. “We have bought some natural enemies. This month, I will travel to South Africa to collect the specimen for trials,” he says.

What about short-term options?

Experiments have revealed some chemicals that well-off farmers can use to get temporary relief as well as some tree species that withstand the pests and give reasonable yield.

Tolerant alternatives

Tembo Chanyenga, the acting head of Frim, is spearheading this search for resistant and alternative trees.

He says: “The attack of the three pests has been so sudden that it is not easy to come up with quick solutions. But farmers should be encouraged to start planting other species both exotic and indigenous.”

He reckons field research has shown that some blue gums, especially eucalyptus maidenii, Euclayptus dunnii and Eucalyptus urophylla, are either tolerant or resistant.

The Frim team is still conducting research to select best chemicals farmers can use, but systemic pesticides—especially rogor (also known as dimetheote) and confidor—have shown early glimpses of effectiveness.

“The chemicals are costly and only effective for a short period of time. New infections would always occur later on. This means the farmers have to repeat the application to ensure they keep the pest population low. Well-off farmers can try them,” he says.

As the pesticides test continues and the country counts down to introduction of the imported killers of pest, planting new trees remains the most affordable and reliable remedy.