Robots could eat all jobs in africa

Nearly all jobs in Ethiopia, and more than half of those in Angola, Mauritius, South Africa and Nigeria could be taken over by automation, according to an incisive new study, throwing a big spanner in continent’s hopes of manufacturing its way into prosperity.

This is because the majority of jobs in those countries are either low-skilled or in industries highly susceptible to computers and robots, including the continent’s mainstay agriculture.

The study, which draws from World Bank research, is authored by United States (US)-based bank Citi and the Oxford Martin School, a research and policy arm of the University of Oxford. It finds that 85 percent of jobs in Ethiopia are at risk of being automated from a pure technological viewpoint, the highest proportion of any country globally.

The study is part of a continuing series on how rapidly changing technology will affect economies and societies as we know them.

In an earlier study co-authored by Oxford University academics, the growing of cereals and fibre crops were found to be near-certainties for take-over by machines and industrial robots—with agriculture generally having the highest risks in a survey of over 700 jobs.

International Monetary Fund data shows that some 90 percent of the 400 million jobs in low-income countries, the majority of which are in sub-Saharan Africa, are in the informal sector—essentially agriculture and self-employment.

In fast-growing Ethiopia, agriculture is the biggest employer, while South Africa’s crucial automotive industry accounts for one in every 10 of its manufacturing exports. The automotive industry is one of three highly robotics-intensive lines of industry, and is at risk because the cost of robots, which was initially a barrier to entry, is now declining sharply.

Losses of already scarce jobs to automation could leave African countries searching for new growth models, just when they thought they had finally found one that works—by turning on the jet packs on industrialisation.

For a long time the conventional thinking has been that African countries can take the historical path to wealth through industry biased towards export-led manufacturing. It is a model that has worked before: for many countries, adopting new technologies has anchored their growth strategy—from the Industrial Revolution and the post Second World War spurt in the West, to the Asian Tigers between the 1960s and 1990s, and China in the last 20 years.

Smart development

These countries moved workers from labour-intensive production to more capital-intensive products such as making motor vehicles, and then onto human capital-intensive activities such as information and communication technology. Now the new buzz is about a “4th Industrial Revolution” which was the theme at the World Economic Forum in the Swiss ski resort of Davos recently.

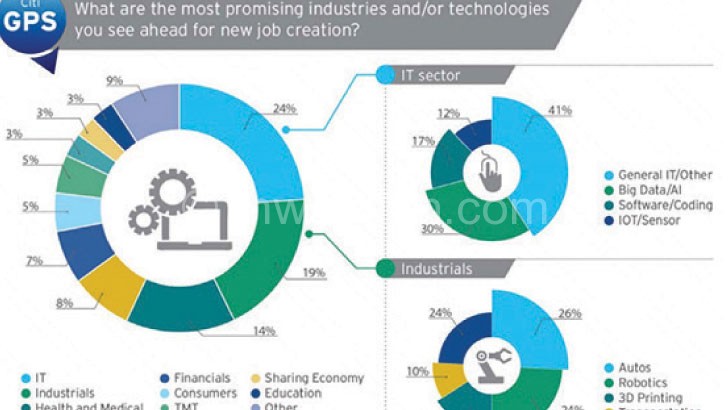

This new revolution will now be about “smart” development that makes things easier—think the Internet of Things— and which brings together previously disjointed fields such as artificial intelligence, machine learning, robotics, nanotechnology, 3D printing and genetics and biotechnology, all which build on and amplify each another.

In Africa, which is still battling many basic structural bottlenecks, this path has in recent years taken the form of investing more into currently labour-intensive agriculture so that it becomes productive enough to move more people into higher-paying industry and services.

This is to an extent been happening on the continent, but it has largely been at the expense of skills, various studies note.

Once people are in the factories, their higher productivity—up to six times that of agriculture and twice that of services— yields increased earnings that are ploughed back into infrastructure, services and education, creating a virtuous growth cycle.

Ethiopia for example now invests the biggest portion of its budget on agriculture, and as a result the country of nearly 95 million people has the world’s highest contingent of extension workers. The investment is necessary because despite having one of the world’s highest growth rates, food security remains the country’s Achilles Heel.

But the Horn of Africa nation has started to show up on the manufacturing radar—a survey by global consultants McKinsey & Company found that for the first time, an African country—Ethiopia—was being picked out as a top destination for apparel-making firms, being mentioned in the same breath with the likes of Bangladesh, Vietnam and Myanmar, as they all picked up after an increasingly prosperous China which has been shedding low-wage manufacturing jobs to cheaper destinations.

Cheap labour has been part of Africa’s marketing pitch to foreign investors, promising high returns for footloose manufacturers, and through this carving for itself a path to rapid economic growth in line with the Agenda 2063 blueprint drawn up by the African Union.

But the new study shows that even this path is now a double-edged sword: today’s manufacturing has already become more automated, and thus has less jobs available now, true of the world over but more acute in Africa. The continent’s share of manufacturing employment is already small—just six percent of all jobs according to the UN’s Economic Commission for Africa (Uneca), against a comparable peak figure of about 15 percent for most emerging economies. The continent also holds only a two percent share of global manufacturing (itself a decline from three percent in 1970).

Additionally, globalisation has further exposed African countries to cut-throat competition that has showed up the continent’s higher costs of production due to an infrastructure deficit.

The study further finds that wage differential advantages are no longer as much of a factor— in the advanced economies of the US and China, recent developments in robotics and additive manufacturing are allowing their firms to bring (automated) production much closer to their domestic markets, thus cutting costs and reining in the offshoring of jobs.

“In the light of these technological development, industrialisation is likely to yield substantially less manufacturing employment in the next generation of emerging economies than in the countries preceding them,” the authors say.

“In other words, today’s low-income countries will not have the same possibility of achieving rapid growth by shifting workers from farms to higher-paying factory jobs”.

Despite the higher productivity that automation portends, it all leaves Africa, which desperately needs jobs for its 1.1 billion people, in a precarious position as rapid changes in demography weigh in.

But it is not all doom and gloom, the researchers say. While these jobs can be automated, it does not mean they will be. This is because it is not economically (and politically), feasible to do so due to the abundance of cheap labour—approaches that save on labour tend to be generally reached for when such a workforce is not available, or if it becomes expensive to borrow against it.

Also, full automation of jobs takes time, even in the developed world, the World Bank says in its 2016 Development report.

“Barriers to technology adoption, lower wages,and a higher prevalence of jobs based on manual dexterity in developing countries mean that automation is likely to be slower and less widespread there [in developing countries].

Indeed when these are adjusted for, countries like Seychelles, Mauritius and South Africa, which are services-heavy, rise to the top of those on the continent most susceptible to rapid automation, reflecting their different stages of development.

But the downside is that this is a temporary situation: when it does become cheaper to automate, the disruption will hit Africa hard given its lower consumer demand and weaker social security safety nets, significantly disrupting society as we know it, as firms such as Uber and Airbnb are showing.

The continent’s policy makers however have the notable advantage of time to anticipate the big change. One way is to boost demand in domestic markets as a shield, the researchers say.

Another is to invest in service-led growth, already happening in many countries. In Ethiopia, services are growing faster than agriculture, while in Nigeria they now contribute just over half of its Gross Domestic Product, outstripping battered oil. In others like Kenya and Mauritius, tourism and financial services are big contributors to the total economic output.

But such service jobs, the majority of which require seeking to help people, are now low-skilled and thus automatable. In Japan for example, robots in some hotels book and show guests to their rooms, while in call centres technology is increasingly handling routine requests.

The more durable alternative is to invest in education that creates higher and better skilled workers, the authors recommend.

“Because skilled jobs are substantially less susceptible to automation, the best hope for developing and emerging economies is to upskill their workforces.”

Jobs that originality, social and creative intelligence, perception of irregular spaces and manipulation are incredibly difficult to automate and thus are at low risk.

Those such as office jobs that require handling of data are not. In other words jobs such as management, healthcare and diplomacy are in; low-skill farming, the post office, logistics, tax and auditing are on their way out.

Investing in more science and engineering, ICT, digital media and the arts provides the continent with the best chance of withstanding a rapidly changing world, the study concludes.—M&G Africa