should malawi have non-political chancellor?

Former University of Malawi (Unima) vice-chancellor Emmanuel Fabiano, during the last Unima graduation, said: “Some government departments give directives to public universities instead of giving advice and guidance through the council.

“It is possible that government does not understand how the university is supposed to be managed, or it chooses to cross the line as it wishes.”

Fabiano said whatever reasons might be given by government, the actions affect operations of the university.

No wonder, during former president, the late Bingu wa Mutharika’s regime, lecturers were locked in a protracted battle with government over academic freedom after former police inspector general Peter Mukhito summoned Dr Blessings Chinsinga, a lecturer at Chancellor College, to explain remarks he made in a public policy class.

Mutharika, as then chancellor of Unima, just could not get the balance of his interests right. Mutharika defended Mukhito to the end, saying the police chief would not apologise to the lecturers.

The battle grounded the college, keeping it closed throughout the eight months that lecturers boycotted classes. Lecturers at Polytechnic joined the boycott in solidarity.

There have been several protests in Unima over poor salaries and general working conditions for lecturers, the death of students such as Robert Chasowa in 2011 under the Mutharika regime, and others which some feel would have been avoided if there was no political interference in the management of the university.

Now there is debate on whether Malawi should embrace a non-political chancellor.

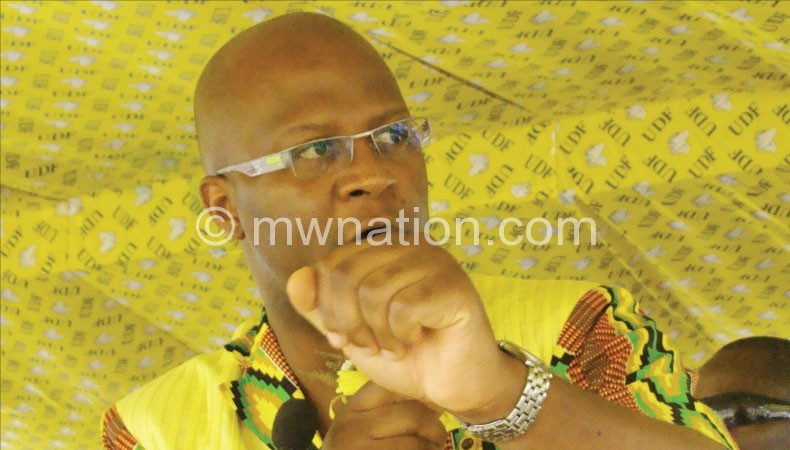

Presidential candidate of the United Democratic Front (UDF) Atupele Muluzi said during a recent public debate at Chancellor College that he would abolish the system where the president becomes an automatic chancellor.

“All problems that are rocking Unima are due to political interference by the presidency. Let there be a technocrat to run the institution for continuity’s sake of different programmes,” Atupele said.

Other countries which have a functional education system such as Britain, Ireland, France and Germany, have technocrats serving as university chancellors. In Africa, Mozambique and South Africa, among other countries, have non-political chancellors for some of the universities.

Unfortunately, the Ministry of Education says although the Unima Act (1998) states that the head of State shall be chancellor of Unima, Section 13 (2), subsection (3) provides for a chancellor who is not necessarily the head of State.

Some analysts say the president finds himself or herself in a position of conflict of interest when he has to balance his or her interests as head of government, head of State, Head of a ruling party and chancellor of the university.

Benedicto Kondowe, executive director of Civil Society Education Coalition (Csec), says trends have shown that the dawn of multiparty democracy led to students to openly express their thought on management of State institutions such as Unima.

“Considering the time that we have had a political chancellor, and the performance of the entities sitting in that office, I am more inclined to think that the appointment should equally be put to test,” he says.

The current University Act does not restrict appointment to the president in that the prevailing law only allows the University Council to invite the president as they would invite anyone to serve as chancellor.

Suggestion of having a non-political chancellor means that the University Council is at liberty to invite anyone as long as that person is competent and of high integrity to serve in that office.

“But since the council is appointed by the president, it has been a tendency that previous councils have attempted only to invite the appointer perhaps to align themselves to the political powers. Unfortunately, none has declined on the possible grounds of lack of commitment or incompetence,” says Kondowe.

Local governance and political expert Henry Chingaipe observes that non-political chancellors of public universities are known to have greatly contributed to the stability and credibility of institutions elsewhere on the African continent, including Uganda.

“The change may also take away the unhealthy motivation of non-graduate presidents who go all over the place in search of honorary doctorate degrees so that they can fit into the designation of chancellor of the university,” says Chingaipe.

Almost all Malawian presidents since 1994 have been given honorary degrees.

However, Minister of Education Lucius Kanyumba told The Nation recently that it is difficult for government not to interfere because the university is funded by government.

“Unima gets funds from government; hence, it is supposed to get involved in the operations of the university. However, it is indeed important for Unima to be independent. But first of all, we should make it financially independent so that it continues to progress,” said Kanyumba.

But Atupele says it is a question of government’s commitment. He agreed that the current situation where the sitting president is chancellor has created problems for the institution whenever lecturers, students and government have differed on policy and other issues.

“I don’t think it will be wise for me to cling to the position when history has shown that academic freedom is affected. Furthermore, funds channelled to the entity are abused,” said Atupele.

In real terms, the appointment is not new globally, and surely Malawi will not be an exception. For argument’s sake, imagine whether it would be realistic that a single person would competently serve as chancellor assuming all the six dream universities were up and running.

This would be practically impossible as the presidency office is a busy office, and certainly it might happen that the person sitting in that office is not even interested in education.

Additionally, President Banda, for more development and research, said her government intends to delink constituent colleges of the University of Malawi so that they are independent, which means the president will be chancellor of each of those colleges.

The Ministry of Education spokesperson Rabecca Phwitiko says government is committed to improving the quality of education in public universities, including Unima as it has been reflected in the National Education Policy of 2009.

“Government continues to provide adequate resources considering the economic realities of the nation. Furthermore, Capital Hill attempts to harmonise conditions of services within certain parameters,” she says.

Chingaipe says one of the implications of having a non-political chancellor is that there has to be a credible process and body for appointing chancellors of the universities. The process may have to include the Public Appointments and Declaration Committee of Parliament.

“The second implication is that the change may insulate universities from misguided policy decisions such as selection quotas, parallel programmes and others that were done for political reasons without considering the other factors that matter in running universities and maintaining excellence and credibility of tertiary education,” he says.

But what could be the organisational structure?

Kondowe thinks the issue of structure should be harmonised as the current Act gives powers to the council to invite any person to serve as chancellor.

“But with the set-up of the Institute for Higher Education, it would make sense that this body should be eventually charged with the role of appointing chancellors. The council should then become accountable to it. But the Act needs to be reviewed to accommodate the Institute for Higher Education,” says Kondowe.

For Chingaipe, university management and policy bodies should be insulated from partisan politics. He says an independent regulator of tertiary education will be able to set standards and procedures that guarantee that university management is free from obnoxious politics.

Phwitiko says Section 33 of the Constitution of Malawi states that every person has the right to freedom of conscience, religion, belief and thought, and to academic freedom.

“Additionally, the government recognises that all academic matters rest with senate committees and government does not interfere in the affairs of senate,” says Phwitiko.

Kondowe suggests that Malawi could learn from other countries as to what the setup is like to the appointment of non-political chancellors.