Slums grow as councils snore

Risky slums are expanding contrary to time-honoured by-laws and policies, our reporters AYAMI MKWANDA and JOHN CHIRWA write.

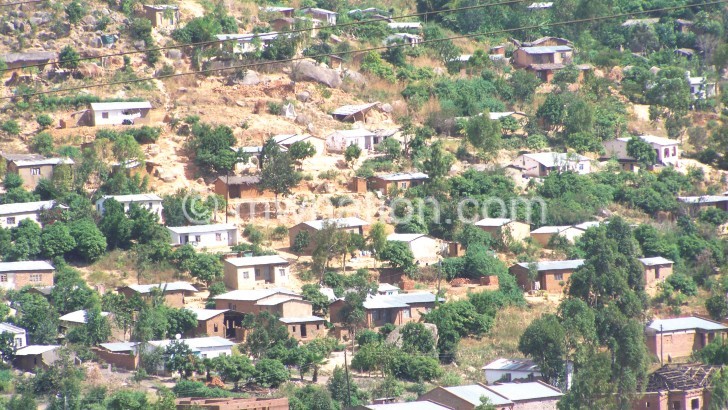

In Blantyre, Soche Hill towers into the sky. Walking up the hill stripped of trees, the uncertainties of slum dwellers on the steep slopes personify silent, but ever-growing scrambles for land as urban populations keep rising.

No planning. No water. No electricity. No road. No law enforcers. No peace of mind.

The inhabitants of the homes overcrowding the hillside where flush floods and landslides displaced 162 people in May 2015 trust no visitor.

Soche Hill offers a bird’s view of the extensive, populous townships of Chilobwe, Chimwankhunda and Manja at the bottom.

On our way up from Chilobwe Market, most occupants fix their eyes on visitors in awe. Others peep through the windows and speak in hushed voices, holding their breaths as if some danger is lurking.

“Maybe, they think every stranger is a detective or city council official,” says our guide.

As we hike the rocky terrain, people are seen moulding bricks, building houses and marvelling at massive kilns of burnt bricks.

Throughout the 20-minute walk, numerous foundations and houses under constructions confirm the mushrooming of new homes in what remains a restricted zone. The slum is growing.

Time check is 11.03am. Our destination is a small home to a family of five. Esther Bwaila, 32, looks terrified. At first, she refuses to speak to us as her husband is off to Chilobwe Market where he operates a shop.

In fact, it takes a family friend of the Bwailas to convince her to open up about their livelihood from their lofty perch.

“I saw you coming, but I was frightened,” she says. “I had to ascertain you are not city officials who want us to vacate the hill. Where will we go?”

According to the mother-of-three, the family acquired the plot in 2013.

“We paid village head Chisa K65 000 for the land,” she recalls.

There are over 400 households who bought their plots in similar fashion notwithstanding that the Local Government Act outlaws the existence of chiefs in the city. Besides, only the councils, Department of Lands and Malawi Housing Corporation are supposed to have control of land in cities.

But the laws fall flat at the foot of this hill. Going up, no one minds the law—and the slum is growing as city authorities and law enforcers look on.

Bwaila explains: “When I settled here, there were blue-gum trees [eucalyptus] on these slopes. They have all been cleared to pave the way for homes. We only hear on radio that the council doesn’t want us to occupy this place. If they want to drive us away, they should compensate us,”

In 2014, a magistrate court in Blantyre ordered 64 families to vacate Soche Hill within six months.

Three years on, Blantyre City Council (BCC) spokesperson Anthony Kasunda says plans to enforce the Magistrate Jean Rosemary Kayira’s verdict failed as more families occupied the hill.

Scores of homes are taking shape although the Bwailas and their neighbours know they occupied the area illegally.

The council seldom cracks down on illegal settlements.

According to Ministry of Lands, Housing and Urban Planning spokesperson Charles Vintula, it is illegal to occupy or distribute fragile zones.

But some self-styled chiefs keep selling land.

Desperation for land is mounting due to rapid population growth as rising numbers of people escape poverty in rural areas.

Besides, authorities’ laxity to enforce existing laws has seen illegal settlements flourishing.

To BCC town planning and estate officer Costly Chanza, the main problem is complicated as more people migrating to cities for greener pastures.

“The council does not encourage squatters, he argues. “We have been relocating them to South Lunzu, but they keep coming back.”

But the rise of squatters on the city’s hills— Ndirande, Michiru, Bangwe and Soche—makes people paid to bring sanity in the country’s cities look hapless and hopeless.

This puts lives at risk. On January 3 2015, a nightly torrent ripped the homes of James Chinthenga and his neighbours in a risky settlement up the highly deforested Ndirande Mountain.

“It was a shocking. We watched the house crumble as we stood in the rain to save our lives, but there was no time to save my property,” he says.

Just last year, landslides in Masasa Township in Mzuzu killed seven people.

Yona Simwaka, a town planner at Mzuzu City Council, said the council has no capacity to remove “an overwhelming population living in undesignated areas”.

“Enforcement of by-laws remains a challenge as the council does not have enough resources to relocate the families from slums to authorised places,” he says.

According to the official, the council intends to relocate 1 500 families from Masasa to Katoto Area Six.

Equally defaced by population pressure is the capital, Lilongwe, where heavy rains displaced thousands in Mtandire slum and other disaster-prone areas this year.

According to Lilongwe City Council spokesperson Tamara Chafunya, plans are underway to resume a programme to distribute affordable plots to low-income earners to minimise illegal settlements in disaster-prone settings.

However, all cities—Lilongwe, Zomba, Blantyre and Zomba—have been petitioning government to extend their boundaries to accommodate people.

Descending Soche Hill, we drove to Blantyre commercial business district where burly BCC rangers ruthlessly hound helpless vendors, especially women, and disposes them of their mechandise, to restore sanity on the streets.

This is the urgency lacking to keep slums in check. As city authorities snore on the job, slums soar. n

Pa phiri ili oneday padzakhala landslide .. athu adzafa pazinthu zoti the council can prevent it at early stage.. please acity simungapange dongosolo? Kodi ndekuti akulu akulu acity mumaganiza bwanji?