The lost glory in education standards

A few months ago, a video clip of Malawi’s youngest legislator, Fyness Magonjwa from Machinga, grappling to fluently speak English in a television interview went viral.

The video clip attracted public attention with some people poking fun at her inability to master the foreign language.

While many laughed, others had a holistic view beyond this incident. They perceived it as an epitome of an education system which is in tatters and needs urgent redress.

With a myriad of other Malawians sailing in the same boat, one therefore wonders, what has eroded the quality of education in the past three decades.

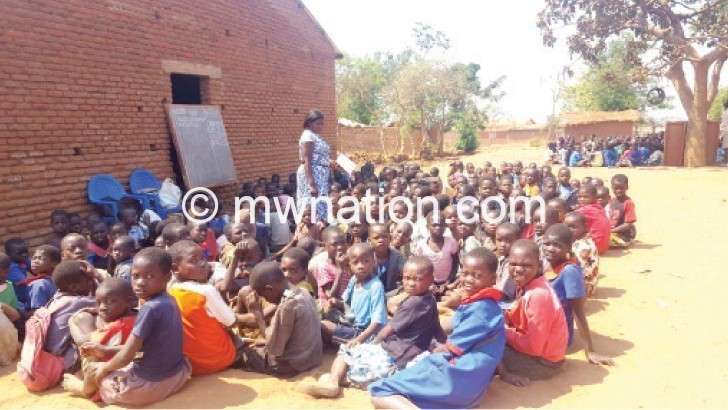

A Research Gate report titled The crisis in public education in Malawi, faults the introduction of the Free Primary Education (FPE) policy which resulted in the influx of new pupils into schools, exerting pressure on existing resources.

The report states that between 1994 and 1995, enrolment grew from 1.9 to 3.2 million students, forcing some students to start studying outdoors and under trees.

FPE also came with teachers’ shortage, forcing government to recruit many under-qualified candidates.

According to the report, out of 45 075 primary school teachers, 23 429 qualified from official training colleges leaving almost 21 646 unqualified and under-qualified.

FPE also resulted in scarcity of teaching and learning resources in schools, which is still a problem even now.

In the same vein, Civil Society Education Coalition (Csec) national coordinator, Benedicto Kondowe faults the introduction of FPE.

He argues that as a mere political directive made on a political podium; it was not supported by any policy, and that in consequence, the country had no clear strategy to deal with free education.

“Government should have quickly developed FPE policy; but it was only in 2015 that they announced the adoption of the national education policy, which in part deals with FPE.

“So we adopted the system without a better plan to address increased enrolment the number of teachers and infrastructure was the same, which increased the number of open air classrooms. And it seems like we have not learnt lessons from 1994 on how best to mitigate those challenges,” says Kondowe.

Weak regulation for schools is another challenge. According to the activist, many private schools opened up in 1994 from kindergarten to university, but the regulation mechanism has not been robust enough to counter substandard education provision.

“It is not only public education which is poor; education is equally poor in some private institutions. So we needed a regulation to tackle that. For the past two years, government has not inspected schools to see if they are viable to accommodate learners. And we have many private schools mushrooming, some even close to bars. So government’s plan to recruit more inspectors was viable but again it borders on political will and money,” he laments.

Kondowe highlights how political will to motivate teachers would go a long way. “We have increased the number of teacher training colleges (TTCs) but absorbing them into the system is a problem. Teachers graduate and spend over a year to be recruited; or if they are recruited, they go for months before receiving their first salary. We need to do better,” Kondowe explains.

Weighing in, education expert Steven Sharra argues that levels in the education systems build on each other in that when one is dysfunctional, the effects are systemic and societal.

“Our problems in Malawi are cyclical. They derive from the size of the economy. But they are also problems emanating from lack of ambition and creativity,” Sharra notes.

He argues that as a catalyst for human capital development, education has a significant role in economic development.

Further, he regrets the school system’s inability to meaningfully educate Malawians, and its incapability to retain them for the duration of the eight year primary school cycle.

“Out of about a million standard one learners, only 300 000 survive to standard eight. And out of these, one in three makes it to secondary school. We have five million primary school learners, 380 000 secondary school students, and an estimated 50 000 tertiary students. The transition numbers are shameful,” he notes.

He observes that the 2019 primary school leaving examinations results with 82 000 learners selected to public secondary schools out of the 218 000 who passed, demonstrates that transition well.

In contrast, the majority of neighbouring countries have nearly 100 percent secondary school transition rates as a matter of policy.

Sharra further notes that although the education sector receives the largest share of the national budget, [at K172.8 billion in the 2018/19 budget] these problems indicate its insufficiency to solve the systemic problems.

However, he considers investing in education as significant arguing the dividend is long term both in economic and social development terms.

He proposes that teachers should be at the centre of national development by, for instance, elevating the teaching profession to the level of prestige enjoyed by doctors, lawyers and engineers.

Both Sharra and Kondowe deem that with political will, issues in the education system can be rectified.

Currently, the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (MoEST) oversees all levels of education and is mandated under the Education Act 2013 (Section 4) to set and maintain national education standards.

Ministry of Education spokesperson Lindiwe Chide concedes the challenges in the provision of quality education in the country.

However, she points out that government has invested a lot in education since 1994, and that it is still investing.

Among other things, she outlines that construction of classrooms is one of government’s main focus through the national budget and various partners.

Additionally, she says government is striving to reduce the teacher pupil ratio by training more teachers and constructing new TTCs to improve on output of teachers.

“We still need more teachers in the system to ensure that the teacher pupil ratio is according to policy recommendation. Classrooms are also still not enough; we need to construct more. We are also having challenges in the resourcing of the curriculum as some schools are still not getting enough materials.

“This is why we are calling on all stakeholders to assist government to achieve its goal of providing quality education. We cannot deal with all the challenges alone,” Chide says.