Transforming lives through village banks

Sylvia Chembe (47) of Saili Village, Traditional Authority (T/A) Makata in Blantyre rural is a hero and a pride of the community.

She is the only woman who owns a grocery shop that serves some 300 people living north-west of the village, 10 kilometres away from Lunzu Trading Centre in Blantyre.

“Previously, we used to struggle to access some of the minor groceries such as matches, soap, sugar, paraffin and salt,” recalls Virginia Semu, a citizen in the village. “Although we still depend on Lunzu Trading Centre for groceries, we need a shop around for small household items,”

The community perched on a hill top has no other means of transport apart from using a small footpath.

The 10 kilometre dusty and gullied stretch is not safe, locals say, especially late in the afternoon as thugs take advantage of the situation to rob pedestrians returning from shopping at Lunzu Trading Centre. That is why Chembe’s shop is ‘a life-saver’ in the area.

“Since Chembe opened the shop, I have not heard of many cases of people being attacked on their return from shopping,” Semu told Business Review.

“The few I have heard is that of people who wake up too early for maize milling at the trading centre. In my case, I go shopping once in a while. When I need small items, I buy them from Chembe. The other advantage is that since we live in the same community, I am able to collect items and pay later,” Semu added.

But for Chembe, the idea to open the shop was not bred to meet the challenges the people in the area have been facing, but to help fill the gap her husband left. Chembe, who is a mother of six says, life became tough when her husband divorced her four years ago.

“Sometimes men have to think twice before they make their decisions. It is not easy to support six children. Life became unbearable and we hardly had three meals a day,” she recalls.

“I could not rely on farming only because I have small piece of land that cannot give me enough harvests for consumption and income. This also happened at a time one of our children was about to start secondary education,” Chembe explains.

She says she needed something to support her family such as business, but a start-up capital was difficult to access.

Chembe recalls that in 2011, she grew some sweet potatoes on her piece of land and when it was harvested, she started to cook some and sell at a nearby primary school, but apart from lack of business knowledge, the returns were too minimal to grow the business and so it folded with the end of the crop at the farm that same year.

It was the following year after Village Head Saili hatched the idea of forming a village bank, that Chembe had hope to revive her dream to own a small business.

Unfortunately, the idea met several challenges as the 15 members—12 women and three men— lacked commitment and to save enough money. Additionally, they lacked technical know-how to manage the village bank. For a year, the group achieved nothing.

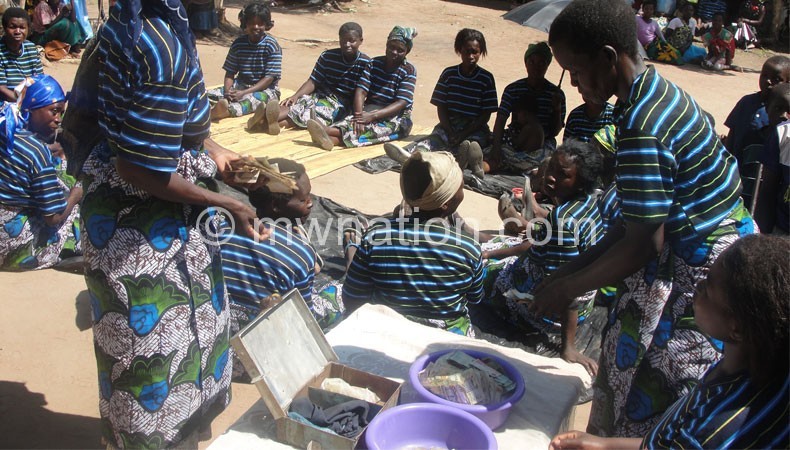

But in 2013, the group resurrected after an NGO A Self-Help Assistant programme (Asap), an organisation working towards empowering men and women economically through access to savings and loans came to the area. It introduced the community to a Right to Access to Savings and Loans (Raso) project that empowers members of the community through village savings and loans (VSL).

“Raso is a three-year economic and social empowerment project targeting to directly transform the lives of 3 600 marginalised people in T/A Makata area. The project has caused a great impact in the community and I am sure by the end of the period, we will talk a different story of success,” TwisiwileMwaighogha, Asap executive director told Business Review.

Asap helped Saili’s village bank to reestablish themselves and start saving their money again. Chembe says they were trained in how to manage their VSL.

“The same year, we saved K151 000 [US$336] which we shared at the end of the year. In 2014, we saved K195 000 [US$433),”Chembe says.

The group, was also introduced to making traditional stoves (mbaula) from soil, which they sold to people within the village and share the proceeds. Each stove sells at K1 000 (US$2).

It is from these two initiatives that Chembe finally realised her dream of becoming an entrepreneur.

Chembe says she realised K50 000 (US$111) which was invested in the grocery shop. At the same time, the group was lent K150 000 (US$333) by Asap through its programme that gives loans to groups practising VSL to start small-scale businesses.

Today, Chembe’s business is one of the most reliable ones in the area and she says the enterprise is now worth about K300 000.

“I am able to pay school fees for two of my children in secondary school,” brags Chembe.

Another member of the group who lead the Mbaula project, Diana Suwale, says the success of their VSL led to the founding of another group, Matiti VSL.

She adds that the Mbaula project has improved the income of the members and consequently increased everyone’s contribution to VSL.

Suwale, who is also divorced, says although they have been selling the mbaula locally, they are able to raise enough money to support their families in addition to VSL returns. She says if they had a ready market, they could produce 500 mbaula in a week.

“Our main market is the villagers, but now almost everyone has mbaula. Unfortunately, mbaula can last for five years or more and it will take time for them to buy another, so we need to find another market,” says Suwale, who through VSL and the Mbaula project has managed to rebuild her house which was destroyed by the recent flooding and storm in Blantyre.

Mwaighogha is happy too that lives have been transformed in Saili Village.

“This is what we wanted to achieve. Over the past six years, we have made differences in a range of areas such as empowering thousands of financially excluded poor women and men to access VSL in the informal financial markets, developed small-business management skills to hundreds of small-scale entrepreneurial operating in the informal business environment. Tafatsa is a model of VSL as we are able to appreciate the fruits of the initiatives,” says Mwaighogha.

He adds that they are working on plans to make the mbaula business a big investment for the group. He says they have found a buyer who will be buying them at a wholesale price and in large quantities.

“Early this month, they sold their products in a bulk and made a lot of money. They are motivated and I am sure, next time they will sell more to make huge returns. We are also working on a plan to have a shop in town where they can be selling their products on retail price,” says Mwaighogha.

As a way of ensuring that the VSL are sustainable, Asap only provides the training at the beginning and some advice sparingly The members perform all the roles on their own. Even the Mbaula project, they manage it themselves. They constructed a production site and each member collects own soil for the mbaula. When this is done, other members come and help the member to mould the mbaula.

While Saili VSL can be a model to learn from, it is not the first. Several other VSLs have been formed and others have collapsed. However, there is still a good penetration of the saving cultures across the country and the fact that formal banking remains a favourable gesture to the few, makes VSL a relevant service to most rural people. Unlike in formal banks where one needs to meet certain conditions to be a member, VSL is open to anyone and everyone saves depending on what he or she has and depending on the conditions of the grouping, there can be interest on money borrowed or not.

Additionally, the money is accessible anytime and circulates within a specific community as is happening in Saili Village—where one borrows money from the group and buys groceries from business- people within the areas.

Economists argue that cash flow within communities improves livelihoods and it is only a person with cash who is empowered and motivated to support national development. With poverty level still at its worst as most people live on less than a dollar, according to Demographic Health Survey (DHS), VSL is a way to go as it apart from improving economic levels, empowers families economically.

“We are focusing on women because they are largely relegated to more vulnerable circumstances because of poverty, but we do not want to leave men behind, hence ensuring there are few men in the groups. We want to see cash flowing and each member being able to meet the basic needs of a family without working for anyone,” says Mwaighogha.