Tricked to work: Plight of child house helpers

She is just 13 years old but has been employed for about two years now as a household helper and does any work to keep a home of seven running.

This is the story of Melina (not real name), who works as a house helper in Chilomoni Township, Blantyre.

Melina, who comes from Traditional Authority (T/A) Njema in Mulanje looks like any other girl as she draws water at a kiosk in the township’s Mulunguzi area.

With a 20-litre bucket of water suspended on her head, she walks happily towards home, cracking jokes with friends from neighbouring houses who are on similar errands.

At first, you would think it is a one-off trip to the kiosk, but no, she is to make nine more trips to fill a 200-litre container at the house.

“I do this every morning when taps are dry. We have a big family and for me to clean the house, wash clothes and ensure that everyone has had a bath, we need more water,” says Melina.

Her day begins at 3am and ends at 10pm. The first task, she says, is to boil water on a charcoal stove (mbaula) for bathing as family members prepare for work and school.

As the water heats up, she sweeps around the yard. By 6am, she starts mopping the dining and living rooms and ensuring that breakfast is ready.

Melina says the only time she at least rests is when the parents and children leave home—leaving her to care for the last born in the family, now aged 17 months old and dropping lunch for two children at a school in Namiwawa Township, about three kilometres away.

Apart from the chores, Melina, a Standard Four drop-out, says instead of resting over the weekend, she runs the family’s small business—a grocery shop although on engagement the agreement was that she would be doing household chores and taking care of the baby only.

She also says her boss told her mother that she would also be sent to school.

Although, there is an arrangement that she should be paid at the end of the month, Melina says sometimes she gets her wage after two months.

She said, currently, her boss owes her wages for three months—from last year, adding that her wage increased by only a K1 000—to K6 000—but because of the arrangement that her employers would send her to school, they deduct K1 000 every month; hence, she gets K5 000.

“They always tell me that they are working on a plan to send me back to school that will not affect the care for the last-born child, and I am just waiting for the day I will be back in class,” says Melina who aspires to become a lawyer.

Section 22 (1) of the Employment Act says no person between the age of 14 and 18 shall work or be employed in any occupation or activity that is likely to be (a) harmful to the health, safety, education, morals or development for such a person or (b) prejudicial to his attendance at school or any other vocation or training programme. At the age of 13, Melina is not supposed to be employed.

Section 55 of the same Act, says it is an offence to pay an employee a wage that is below the prescribed statutory minimum wage. The Act also says each employee should work for a maximum of eight hours a day.

Last year, government revised the minimum wage from K551 to K687.70 per day.

But how did she find herself in this?

Melina says she comes from the same area with her employer and she got the job through her brother.

“Before I left, my parents had a long chat with my employer on phone and it was then that she promised to send me back to school.

“She said I would be part of the family. I was happy, but now I feel that I am being overworked and abused. If they do in send me to school in two years, I will leave,” says Melina.

At the time of compiling this inquiry, Melina had reportedly secured a similar job at Fargo Area, in the same township.

She is the last born in a family of five. Her two sisters—aged 15 and 17—are married. One of her brothers, aged 19, operates a bicycle taxi at Muloza Border while the eldest, aged 23, works at Limbuli Tea Estate in Mulanje.

Melina says none of her siblings reached Standard Eight and claims nothing but poverty drove them out of school.

Eye of the Child executive director Maxwell Matewere describes Melina’s case as child labour and attributes the rampant increase of such practices to, among others, lack of political will, poverty, orphanhood, harmful cultural practices, limited social services, illiteracy, unplanned pregnancies and weak law enforcement and capacity.

“There are many issues that need to be checked to win the battle. The current labour and employment laws still have huge gaps as the drafters did not take a human rights-based approach. The drafters were supposed o address both legislative and non-legislative elements,” says Matewere.

It is estimated that worldwide, 220 million children are in child labour and 26 percent of them are in sub-Saharan region.

Lovemore Guta, a retired primary school head teacher, says family background has a direct bearing on the future of children.

He says although primary school education was, until recently, genuinely free, poverty still kept some children out of school and forced them to seek employment because of lack of school uniform, notebooks, food and soap. He adds that it is when one is just idle at home that they become victims of ugly circumstances in the quest of sourcing money.

Guta does not blame Melina for the situation she is in.

Child Labour National Action Plan (NAP) data from 2009 to 2016 shows that a 2002 survey by government found that 37 percent of children aged between five and 15 were involved in child labour. Fifty-three percent of these worked in agriculture and 42.1 percent in community and personal services sector. This was confirmed by the 2004 Malawi Demographic Health Survey.

The others were shared among sectors such as retailing, wholesale, quarrying, mining, construction, manufacturing, street work and commercial sex exploitation.

The Republican Constitution protects children under the age of 16 from economic exploitation and work that is likely to be hazardous, that would interfere with education or that is harmful to their health, physical, mental and spiritual or social development.

NAP defines child labour as any employment to an individual under the age of 18 and further states that child labour is any activity that employs a child below the age of 14 or that engages a child between the ages of 14 and 17 and prevents him or her from attending school or concentrating on school, or negatively impacting on the health, social, cultural, psychological, moral, religious and related dimensions

Losing child labour fight to domestic employment

Driving past Chonde and Chitakale trading centres towards Mulanje Boma on a Saturday afternoon, one is greeted by scores of children selling various food items to motorists and public transport passengers.

Most of the group that shout to entice travellers to buy from them are children aged between six and 17.

While some are assisting their guardians, the majority are employed; hence, have to meet daily targets if they are to get their full perks at the end of the month.

A 12-year-old boy we will identify as Jackson is a Standard Four drop-out Exclusive Inquiry met at Chitakale Trading Centre and says he has been selling merchandise on the roadside for three years now.

“I got the job in 2013. My job is to sell any product that the family gives me to sell. I sell boiled eggs, flitters, snacks, soft drinks, crisps, biscuits, pine apples, cold water, fried chicken, mang’ina and kanyenya (kebabs),” he says.

Jackson explains that he operates from Chitakale Trading Centre and Mulanje Bus Depot, which makes the job hectic.

“It is not safe to do business at Chitakale after 9pm; so, when I feel that I still have more products to sell, I proceed to the bus depot where I target bus passengers in buses to and from Muloza Border. My main customers are parents travelling with children,” he says.

Jackson says his day starts at 8am and ends at 10 pm every day—an average of 13 hours per day except on Fridays and Saturdays when he knocks-off at around midnight.

His situation is in contravention of the Labour Act. Section 37 of the Act says no employer shall require or permit any employee other than a guard or any shift worker, who normally works six days during a week, to work for more than eight hours on a day.

As if this is not enough abuse, Jackson gets paid peanuts. He is currently paid K8 000 per month, which is below the country’s stipulated K687.70 per day minimum wage.

“I needed money to survive and I could not stay in school because of poverty in my family,” he laments.

But he is working illegally, because Section 22 (1) of the Employment Act says no person between the age of 14 and 18 years shall work or be employed in any occupation or activity that is likely to be; (a) harmful to the health, safety, education, morals or development for such a person; or (b) prejudicial to his attendance at school or any other vocation or training programme. At the age of 12, Jackson is supposed to be in school.

Mulanje district labour officer Charles Katembo said the problem engaging children below the employment age in domestic work is serious in the district. He says despite several campaigns, the story remains the same.

“Mulanje has improved in the rates of child labour, especially in agricultural estates, but now what is bothering us is domestic work because employers are preferring children,” says Katembo.

He says they have been holding campaigns to stop people from employing children for domestic work by confiscating merchandise being sold by the under-aged, but says the impact is minimal because the children return to the streets a few days later.

“I think we have the potential to end the practice, but currently our setback is poor funding from the ministry. We cannot reach to all places as we wish due to transport problems,” explains Katembo.

The situation in Mulanje cuts across Malawi.

Mzimba North child protection officer, Chimwemwe Ngwira, laments that there is an increase in the use of children in selling commodities in the streets in his area.

He adds that more serious and risky is the practice of night vending by children because it contravenes Section 23 (4) of the Constitution, which protects childrens from all forms of abuse.

However, Multiple Cluster Indicator Survey conducted in 2006 shows that the prevalence of child labour had dropped by eight percent—from 37 percent. n

Combating child labour in smallholder tea farming

If you take the definition of child labour as only any employment to an individual under the age of 18, then some parents in Traditional Authority (T/A) Mabuka in Mulanje would be applauded for infusing a culture of hardworking in their children.

But the story becomes slightly different when you consider the other part of the definition, where child labour is viewed as any activity that engages a child below the age of 14 or a child between the ages of 14 and 17, preventing them from attending school or concentrating on school, or negatively impacting on the health, social, cultural, psychological, moral, religious aspect of their upbringing.

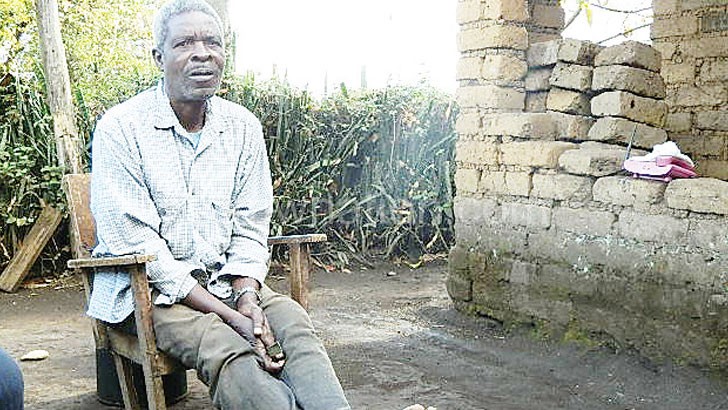

Ceaphas Bondo, 41, of group village headman (GVH) Ndaonetsa is one of the people who value the importance of imparting knowledge about farming to children.

Widowed, with four children, Bondo says he dedicated five years from 2012, teaching skills to his children to ensure that they are self-reliant in future.

But Bondo’s act can be construed as enhancing child labour when he engages his children in his half-acre tea plantation year-in, year-out.

“At this age, I cannot farm alone, I need the children to support me because if we employ people, then it means more money will be going to them. I make sure I introduce the children to the plantation’s activities while they are still young because life in Mulanje is about agriculture and the key crop is tea. Even when they grow up, the available jobs are in tea estates,” explains Bondo.

But Bondo’s children are not supposed to be engaged in any form of work aimed at generating income, according to the country’s Labour Laws. Section 22 (1) of the Employment Act says no person between the age of 14 and 18 years shall work or be employed in any occupation or activity that is likely to be; (a) harmful to the health, safety, education, morals or development for such a person; or (b) prejudicial to his attendance at school or any other vocation or training programme.

Just metres away from Bondo’s house lives GVH Ndaonetsa, who also engages his children and grandchildren in tea farming activities. He told Exclusive Inquiry that he is preparing the children to take over from him.

“We want them to learn and be able to take over. During the rainy season, there are too many tea leaves [ready for plucking] that parents alone cannot afford and so we are engaging the children. I just make sure that they go early and knock-off in good time so that they can go to school. Sometimes, they go in the afternoon and we sell the leaves the following day. This is our only source of income. They know that we rely on returns from the plantation for them to be in school; hence, it is the will of everyone to support the family venture,” says Ndaonetsa.

International Labour Organisation (ILO) describes work in plantations such as tea estates as hazardous because they are labour demanding, depending on chemicals and fertilisers that are hazardous to human health if no proper care is taken while fields have stem stumps that can cause injury.

Bondo and GVH Ndaonetsa, who are smallholder farmers, admit that they can hardly afford gumboots, raincoats, gloves and other protective gear for the children.

Mulanje district labour officer Charles Katembo while acknowledging that tea estates are complying with the requirement of not using children in estates, the story is different with smallholder farmers as shown by the survey.

“I can say most estates have stopped hiring children to work for them, but if you go to tea fields owned by smallholder farmers, especially during the harvest season, you will find many children in the farms. I was shocked when I went to Ndaonetsa area with officials from Capital Hill to appreciate the child labour situation. We found children as young as 12 plucking tea and others helping their guardians weighing the crop. Had you come during the harvest season, you could have appreciated what I am saying,” says Katembo.

He says his office has been engaging traditional leaders in the district to ensure that no one employs or uses own children in tea fields, but says the outcome is not encouraging.

Katembo attributes high levels of child labour in tea fields to poverty and culture.

“Our culture is the biggest problem. There are too many unplanned marriages because most girls after initiation feel they are old enough and start sleeping with men. In the process, they become pregnant. Most marriages are collapsing and when this happens, the divorced or widowed women go to estates to look for jobs,” he explains.

Katembo says there is a lot to be done to win the battle against child labour.

While age-cheating is a serious hurdle, Lujeri Tea Estates says it has won the battle against it in its estates, but accepts that there is still some smallholder farmers affiliated to them who still engage children below the employment age in their fields.

Davis Mathanda, personnel and administration manager for Lujeri, says they have invested a lot in fighting child labour, adding that for the past 10 years, they have not registered any child labour-related case.

“We are affiliated to Fair Trade, an international association of agro-producers that also forms part of the markets for our products. There are conditions that satisfy a company to be registered and child labour is one of them. They audit us annually and our records are clean on child labour. We just want an extra gear to monitor our smallholder farmers because what we are gathering is that some of them take to their fields children in the early hours of the day, so that we do not see them. We are promoting farmer-to-farmer monitoring and we will be awarding those that report to us those farmers who are still engaging their children,” explains Mathanda. n

When sex work becomes child labour

In the heart of Chirimba Township in Blantyre, stands a haven for imbibers and an asylum for both young and adult females available to service men looking for cheap sex.

It is a typical environment that depicts an experience at a drinking place where you do not expect decency to define business.

Visiting for the first time, you would think you are in a rural set-up as you are greeted by dirty children carrying empty packets of opaque beer collected from within and young girls dressed in ordinary dresses or skirts and blouses.

Also welcoming you is an irritating smell of urine from nearby toilets.

As you spread eyes from one corner to another, you start appreciating that the arena gives out more than the liquor. Sex, cheap one is available.

A bubbly young girl below the age of 15 welcomes one of the men visiting the place for the first time, briefing them on what is on the menu as they drag one of them onto the dance floor where you see the girls wriggling their bodies seductively to entice the customers.

There are girls of all ages, but selling like hot cakes, are the very young ones. In pairs, people disappear to rooms behind the building. For teenagers, there is no resting as demand surpasses supply. There are different men—some coming for a drink, others just to get cheap sex.

With the help of one of the oldest sex workers, Exlusive Inquiry engaged one girl, aged 14. We call her Fortunate because of her age. She has been operating at the joint for about two years now and explains that she works as a bar tender.

“My duty is to serve customers, but when I find a customer, I sneak to the rooms, service him and resume my work,” says the girl.

While other sex workers, who put up at the drinking joints’ rest houses pay K1 000 for the rooms, this young girl lives in one of the rooms for free. She says they are privileged to have a free room which she says she sells for short-time service to those who just come to demand sex.

She is not alone. She explains that she came with two others and one operates from a nearby drinking joint. They were trafficked into sex by their aunt, who is also a sex worker.

“We were picked by an aunt who introduced us to the place. She had a house where we all lived. We used to operate as independents, but we all contributed towards running of the house. But there were problems and so we separated. I don’t know where she is. This is why I secured a job here to easily manage myself,” claims the girl, who says she comes from Makwasa in Thyolo.

She works seven days a week for a maximum of 10 hours a day. She explains that she goes to bed when the bar closes and when all imbibers have gone home.

“Sometimes, especially on Mondays and Thursdays, the place closes by midnight, but during the end of the month, business goes as far as 4am,” she says.

The girl works everyday and says she earns K7 000 a month.

Fortunate is in child labour and claims they were told to lie about their ages when the police visit the premise.

Our investigations find that operators of drinking joints at the premise prefer young girls because they attract customers.

In Blantyre, drinking places in townships such as Kachere and Bangwe are usually ‘serviced’ by underage sex workers.

Our sister paper Weekend Nation of February 28 2015 exposed a syndicate of child trafficking and use of girls for sex at Mama’s Shabeen in Ntcheu, where minors as young as 12 were being employed to sell sex.

International Labour Organisation (ILO) reports that the global number of children in child labour has declined by one third since 2000—from 246 million to 168 million. More than half of them [85 million] are in hazardous work. ILO says Africa tops the list of continents with sub-Saharan Africa being with the highest incidences of child labour, of around 59 million, thus, over 21 percent. n

The route to child trafficking

A 14-year-old boy we will identify as Simbarashe of T/A Mabuka in Mulanje recalls a man walking into their yard, politely asking for the head of the family.

Simbarashe calls his divorced mother to meet the visitor as he walks away to join friends playing football at a nearby school ground, before he is called back home.

“I just heard my younger brother calling me and when I rushed home, I found the visitor with my mother in the living room. There was a private discussion going on,” recalls Simbarashe.

This was the beginning of Simbarashe’s journey into child labour. He was 12 then, and two years at home having dropped out of school.

The following day, explains Simbarashe, he joined a group of 11 boys aged between 10 and 17.

He is the first-born in the family and says his mother spent about two hours with him before departure to convince him to go with the man to Lilongwe for work. The boy said the man who took them had promised them better perks and good houses.

“We are poor and my mother thought that if I got a job, I would help her run the family. She told me we would be paid weekly, meaning I would soon be able to support my younger brothers to go back to school,” he remembers.

The journey began with a 10-kilometre walk from the village to Mulanje Boma where they took a minibus. Simbarashe says the man organised them to act as though they are travelling alone. He adds that he saw minibus drivers pocketing some money in addition to the fares.

Although, the earlier communication meant they were heading for Lilongwe, the boys were being taken to a tobacco estate in Mzimba.

Simbarashe says they used three different minibuses and at road blocks, the driver was dropping off and tipping police officers with some money. He says that happened at four roads blocks along the Muloza-Limbe and Blantyre-Lilongwe via Zalewa roads.

After a night’s travel, Simbarashe says the syndicate was busted in Lilongwe when police officers were suspicious with the presence of so many children in a minibus behind the main bus depot.

He says the man who had taken them disappeared forthwith. Simbarashe and the other children were taken to Lilongwe Social Welfare Office, from where they were later repatriated home.

This case is not exceptional, research indicates that hundreds of children are being trafficked into child labour every day.

Last August, police intercepted a child trafficking syndicate at Wenela Bus Depot in Blantyre in which the child tracker, Mateyu Sali Kuchepa, 40, was taking 21 children to his farm in Mangochi. He had successfully travelled with them for about 80 kilometres, through Muloza-Limbe Road on a bus.

Kuchepa is currently serving a two-year jail sentence. He used the same system of using buses to beat the law and direct approach to parents.

According to one of the rescued children, aged 17, all of them had consent from their parents and guardians as the man promised them good money that could have ended their poverty.

“The man first approached us and after we agreed to go with him, he came to our homes and informed our parents about it,” he says.

Simbarashe and the 11, including nine rescued by Blantyre Police are lucky that they were saved before going into child labour. Hundreds of children in their ages are languishing in different workplaces.

In Blantyre, the social welfare office recently rescued two boys from Mulanje who were trafficked to Chilomoni Township where they were working as house helpers.

Blantyre social welfare officer, Trophina Limbani, is not pleased that the traffickers were left scot-free.

“There have been good efforts in fighting child labour and we have rescued a number of children. However, we have a recent case involving two children that were trafficked from Mulanje. We rescued them with the help of the police, but we did not win the case because we suspect the children were bribed to lie about their ages in court,” says Limbani.

She adds that since the incident, her office has been working with Mulanje Social Welfare to follow up with the children. She, however, referred Exclusive Inquiry to the office to get more details and talk to the children and their guardians, but efforts to engage the Mulanje Social Welfare Office proved futile. n

Retail shops, a haven for child labour

By 6am every day, 16-year-old Limbani (not real name) is on the road walking from his home in Namiyango, Bangwe Township in Blantyre to Limbe.

As a shop attendant, he sells merchandise in one of the shops belonging to Asians.

Although his age is below the recommended employment age, according to the Employment Act and the Child Labour National Action Plan (NAP) which put the employment age at 18 and above, Blessings is not new in the employment sector. Next month, he says, he will clock three years working as a shop attendant.

“I have changed jobs seven times,” he begins the story. “My first job was at a restaurant and my main duty was cleaning the place, plates and serving customers. I quit because we were not being paid on time.”

Exclusive Inquiry found him at one of the Chinese-owned retail shops.

There are five Malawians working in the shop, with Limbani as the youngest.

“Our main duties are to welcome customers and taking them around while telling them prices of commodities where necessary. In the morning, we clean the shop. We have a roaster for cleaning the shop,” he says.

Limbani says the shop opens at 8am, closes for break at noon and reopens at 1.30pm to the close of business at 5.30pm. They work for six days—from Monday to Saturday. He reveals that except for the accounts assistant, they earn K10 000 per month each.

What Limbani takes home is less than the K18 000 set government minimum wage and this is in violation of Section 15 of the Employment Act, which says no employee should be paid less than the minimum wage.

He says employers do not ask about one’s age when hiring people.

“My boss just wants someone who can speak well with customers, and trustworthy. You do not need instruments to measure this,” he argues.

The reporter tried to talk to some of the owners of the shops to give their side of the story, but none cooperated.

During a visit to Lilongwe, we found two boys, aged 14 and 16, helping a woman selling second-hand clothes at Tsoka Market.

“It is just piece-work. They give me K500 and sometimes K1 000 if there is good business,” said one of the boys, who also revealed that sometimes they also carry remaining goods to warehouses for storage at a fee.

Child rights activist Maxwell Matewere says Malawi has policies that can change the situation on child labour.

“We have policies and Malawi signed different protocols which I think can change the child labour story in Malawi. For instance, the Convention on the right of Children (CRC) and the African Charter on Welfare of Children have provided adequate direction in key legal, policy, development and partnership towards the promotion of children right in Malawi.

“It is pleasing to note that the most recently, laws such as the Child Care, Protection and Justice Act(2010), the Marriage, Divorce and Family Relations Act (2015), the Education Act(2012) that provides compulsory primary education, the trafficking in Person (2015) that define the child as a person under the age of 18 and the Constitutional Amendment (2010) that has now provided an order for consideration of the “best interest of the Child” in all matters concerning children. All laws above have domesticated and modelled broadly on provisions of the Convention on the Rights of Children (CRC), and the African Charter on Welfare of Children,” he says.

But Matewere says with these in place, the battle remains at coordinating the key players.

“We need to fully enforce our laws, particularly the Child Care, Protection and Justice Act and strengthening monitoring structure. We need to provide adequate resource in support of cash transfers and enforcement of compulsory education.

“We need to change our altitude and adopt sustainable approach. If we all call for zero-tolerance, we will not see anyone employing children and we will see more actions toward helping the poor children in accordance with the law,” says Matewere. n

Losing child labour fight in tobacco estates?

While on their usual trips to inspect progress on the fight against child labour in tobacco estates in Kasungu district, officials from Plan Malawi recently got what only symbolises a step backwards in the fight against child labour.

As they travelled deep into the main tobacco growing area in Chiwere Village, Traditional Authority (T/A) Wimbe, they were greeted by a herd of cattle crossing the road towards the dambo for grazing.

Behind the herd was a statement of slow progress in the child labour fight. There was a 12-year-old boy (name withheld) herding cattle belonging to one tobacco estate owner. He was on full-time employment and that was just one of his many duties at the farm.

“We stopped the boy and we learnt he was employed. When we took him to the nearby market to buy him clothes and shoes, that is where we learnt about the sad tale that drove him into child labour,” explains Grant Kankhulungo, formerly Plan Malawi’s child protection and participation manager, but now with Oxfam Malawi.

Adds Kankhulungo: “The boy is an orphan. He was left by his mother after she found another husband, who did not want to take care for someone’s child. When neighbours saw the child crying, having no one to look after him, they took him. After some years, the boy decided to go and look for employment to support himself.”

While this boy’s story sounds exceptional as he had no one to support him, many of his age-mates in child labour have parents. Another boy now aged 14, from the same village, shares his experience with Exclusive Inquiry. He reveals that he started doing piecework in tobacco fields when he was eight. He adds that his parents lived on piecework in tobacco fields.

“I was in school, but dropped out while in Standard Three due to poverty. It started slowly with my father picking me along to his piecework. Then, he bought me a small hoe. With time, I learnt digging, weeding, sorting tobacco leaves, packing and loading. It was this time that I started to seek my own piecework to get money for my needs,” he explains, adding that he was rescued by Kasungu District Child Labour Committee (DCLC).

Kankhulungo reveals that while government and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) have rescued many children from child labour, the story on the ground is still unattractive.

“There are reports of employers exploiting children as young as eight and this is worrisome and calls for the need for more effort,” explains Kankhulungo.

According to him, such organisation rely on DCLC and the social welfare office to combat child labour in Kasungu.

With a total land area of 7 878 square kilometres, agriculture is the main activity in Kasungu and it employs over 80 percent of the population in the area, according to a 2011 Plan Malawi Kasungu Child Labour Report. Tobacco is the main cash crop with the largest labour force in the country.

According to 2006 data from Tobacco Association of Malawi (Tama), there are over 22 000 tobacco estates for both commercial and smallholder farming. The report also singles out Kasungu as one with the highest child labour cases in tobacco farms.

Even when chief executive officer for Plan International Inc Nigel Chapman, visited the district in 2011, to appreciate the seriousness of child labour in tobacco estates in the district, he could have done nothing more right than to order Plan Malawi to implement a K20 million project to support Kasungu DCLC on its activities in fighting child labour.

Kankhulungo argues that clear focus, seriousness and better investment, the fight against child labour can be won.

“As a country, we are making progress in child labour fight, especially on raising awareness and data puts it at around 60 percent. However, much focus has been put on those children already found in child labour and not in curbing those who are on the verge of getting into it. Again, there are specific districts which are considered main suppliers of child labour such as Dedza, Ntcheu, Thyolo and some neighbouring areas in Mozambique,” he says.

Although there are no fresh statistics on the level of child labour in the country, results of the 2002 Child Labour Survey are discouraging. They reveal that about 1.4 million children were reported to have been engaged in child labour.

Tama says fresh statistics will be out soon as stakeholders in the fight against child labour are conducting research to establish new figures. However, the association says it is encouraged that it is winning the battle because the threats that are there to end obacco growing are helping them to impart the message on child labour objectively.

“Most of the tobacco estates are on contract with merchants of which cannot buy their crop if they involve children in working on their leaf. In short we are winning,” says Tama chief executive officer Graham Kunimba. n