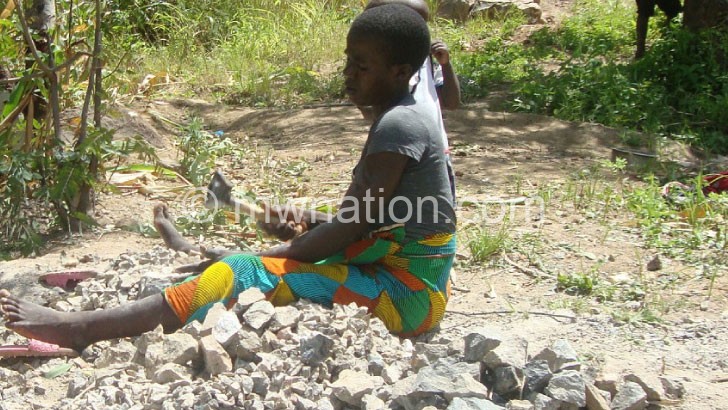

Warning: Women at work

Dawn has just broken in Jingani Village in Rumphi and villagers are emerging from their homes.

As morning chores typified by clashing sounds of kitchen utensils get underway, another hectic day has just begun for some 10 women

They walk to a nearby hill where they roll down heavy rocks to a special spot where they break them to pebbles of different shapes and sizes using hammers.

Most of them are either widows or single mothers sweating profusely to fend for their children.

They are breadwinners in a cultural setting where men mostly play this role.

In May when maize harvesting is over, they take on the hill to crush rocks for sale to people constructing homes in the rural area under Chief Chikulamayembe and surrounding areas.

In their fields, crop harvests are falling due to degraded soils and climate shocks. As such, quarry making has become a means of survival.

“It was difficult for my family to survive when my husband died in 2011. I started a small business to feed and educate my children, but life was never easy,” says Constance Gondwe, 68.

The mother-of-three joined the stone-crushing group six years ago.

“Breaking rocks is not an easy task, but the benefits keep us going,” she says. “My family would have slipped into abject poverty had I folded my arms to wait for well-wishers to raise my children,” Gondwe explains.

Through the business, she earns enough money to pay fees for one child at Chankhomi Community Day Secondary School and two others at Rumphi Secondary School.

Gondwe has constructed a house in her village.

“The rock-crushing business has completely turned around my life,” she says, rubbing her blistered palms.

Esther Nyasulu, 30, who separated from her husband, is equally optimistic. The struggle to raise two children single-handedly compelled her to join the group in 2010.

“After divorce, I had to look after our children and my two sisters, including paying their school fees. The blistering work helps me take care of them. I now own pigs purchased using the proceeds of the job once dominated by men,” she states.

Rumphi district social welfare officer Joshua Luhana says breakdowns in the extended family system has left widows and divorced women with “nowhere to run” for the care of their children.

The extended family system prevalent in Northern Region requires the next of kin to take care of women and children without a breadwinner.

When death strikes or marriage breaks down, a woman bears all the brunt of raising the children single-handedly.

Luhana explains: “When parents separate without going through the court process, the issues of wealth distribution and maintenance of children are not taken into consideration. The children are left with the mother.

“The father can marry again and continue living his normal life without considering the welfare of the children left in the care of his former wife.”

Unlike Gondwe and Nyasulu, Jane Nyirongo, 27, is neither divorced nor widowed. She is jobless and has no skill.

The mother-of-two also scales the hill to turn around her economic prospects to make quarry for sale.

She has been breaking rocks and selling quarry for six years.

“When I saw my fellow women cashing in from the sweat of breaking rocks, I felt compelled to join them instead of just staying idle and begging money for small things from my husband,” explains Nyirongo

She has bought a plot where she intends to construct a second house.

“Since I started selling quarry, my life has really changed. I take care of my family. I have built a house where we are living,” says Nyirongo.

However, it is draining to push huge rocks downhill and to hammer them to size.

At the end of the process, the women carry bulky buckets loaded with heavy stones on their heads to their selling points.

The booming construction industry to meet housing needs of a fast-growing population as well as public and private firms supposedly provides a ready market for quarry stones.

But the women with hammer in hand sometimes spend a month without making a sale, compelling them to engage middlemen who get a cut from any successful deal.

“We often rely on agents to find customers, but this eats into our profits,” Gondwe bemoans.

From their back-breaking occupation, the women have lofty dreams to venture into more lucrative businesses that would lift them out of poverty.

“How I wish we could stop doing this tiresome business, but we need some capital to start better businesses. This one only requires my energy,” says Nyasulu.