Where are the trees?

There are several interventions to protect forests and their trees, but it seems deforestation is winning. ALBERT SHARRA writes.

Slowly, Saili Hill situated north of Traditional Authority (T/A) Makata in Blantyre Rural is turning into a desert as people have cut down trees for settlement and farming.

Just two decades ago, says Mwaiwao Botolo, a resident of Saili Village at the bottom of the hill, the highland had a thick natural forest.

“This was one of the biggest forests in Blantyre north-west, but it is all gone now.

“Since the early 1990s, people would come from various parts of Blantyre to source timber and burn charcoal. There was no one to stop them,” Botolo says.

Today, one can hardly see a tree on the hill.

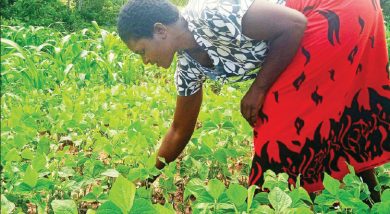

Another villager, John Francis, 53, says the situation has created artificial bare land which people have turned into farmland.

“Population continues to grow, but the land is the same. We rely on farming and when I saw that there is no land, I moved upland and that is where I built my house and started farming,” says Francis.

Saili Hill is one example of forest land that have been depleted. From Chikangawa Forest in Mzimba to Mulanje Mountain, deforestation has left the land bare.

People in Mulenga Village, T/A Mphuka in Thyolo are the main beneficiaries of mountain land, but they are learning the hard way about effects of deforestation. Chief Mulenga laments that rainfall in the area has drastically reduced.

“People now walk about 15 kilometres to the other part of the mountain where Satemwa Tea Estate has forests of indigenous and exotic trees, to fetch firewood. However, they do not get the firewood easily as they have to face the estate’s forest patrol. Even to access timber for house constructions, they rely on stealing from the forests at night,” says the chief.

He confirms that many of his subjects have spent nights in police cells after being caught stealing timber.

“We have created a problem we can hardly solve,” laments the chief, adding: “Most people did not understand the implications of destroying forests.”

He recalls how, a few decades ago, the mountain used to be a source of pride among the villagers, providing firewood and where some could hunt animal.

A State of the Environment Report by the United Nations shows 47 percent of the country was covered by trees in 1990, but about 17 of every 100 trees were gone by 2010. Malawi’s annual deforestation rate is estimated at around 2.8 percent, the worst in Southern Africa Development Community (Sadc) region and fifth globally.

Breakdown of the rates of deforestation across Malawi gives shocking figures. For instance, Zomba-Malosa and Liwonde forest reserves lose one million trees to deforestation per year, according to the district’s forestry officer Paul Muhosha.

During the launch of this year’s tree planting exercise, President Peter Mutharika said: “Mankind is paying tragic consequences everywhere. We need a soul-searching on what happened to village forests, green hills and mountains, which provided fruits for essential immunities and medicine.”

Mwisho Ndini, a graduate in forestry, blames the damage on weak laws on protecting the forests.

“Why should we watch forests being depleted like this? Should one just walk into a forest and destroy trees, go scot-free or just pay peanuts in fines?” wonders Ndini.

As argued by forest experts, deforestation cannot be stopped completely in Malawi because its population mainly depends on timber. But government adopted a ‘cut one tree and plant two’ campaign to encourage communities to plant trees. In addition to this is the annual tree planting exercise.

Every year, government plants about 60 million trees. But where are those tree? n

Next: How much of the planted trees are surviving? Are they making any impact?