Whose interest is toilet business?

The sun sinks below the skyline and darkness is looming over the commercial city of Blantyre.

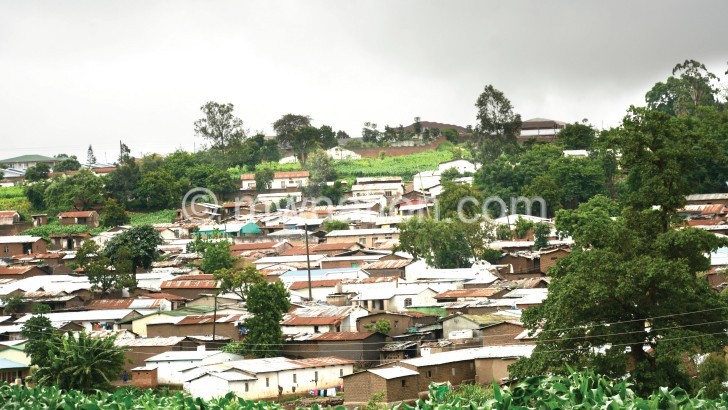

Some residents living without a private toilet in Soche, a low income informal settlement bubbling with rapid population growth, prepare to conduct what is now seen as a daily ritual

Every day, when darkness falls, residents without toilets in low income urban settlements across the country, slip into nearby church or school toilets or their neighbours’ outdoor pit latrines, or worse still squat along pathways and in bushes to empty their bowels.

Onlooking neighbours say most people who do this are migrants from rural settings, who do not have toilets and have stubbornly stuck to practising open defaecation because they consider using the toilet as filthy and not a necessity.

In a five-member family in Soche, three of the household’s children (aged below 15) use their neighbours’ latrine. If it is not engaged, the children’s parents also use it but only at night. Otherwise, they have to walk some distance to access a toilet at a church or school, and if not, they end up in a bush.

Combined monthly small-scale business earnings of the husband and the wife, both of whom did not go past their junior secondary education, do not satisfy the family’s daily needs. Meanwhile, they do not consider constructing a pit latrine an immediate priority than investing in food and other household necessities.

A simple latrine has a pit covered by a floor of mud or cement. Its

walls are made of stalks, mud and sticks, mud bricks or grass without any reinforcement and may have a roof of iron sheets or sticks and grass. The design and cost of constructing a latrine reflects the materials and labour used, and may sometimes also reflect earning levels.

A few kilometres away in Nkolokosa, a planned township, live families with state supplied sanitation infrastructure systems including a sewerage connection.

The scenario draws a picture of status with the wealthy whose excreta is washed away by a State-provided sewerage system being regarded worth State-sanitation intervention while the poor, who lack toilet privacy and live next to their own faeces, are invisible to any State intervention and are left using un-serviced and own-built pit latrines or even worse still to use plastic bags or buckets to defaecate in the open.

The plight of the poor replays itself in different ways despite national governments agreeing under the 2015 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), commiting that sanitation services are a legal entitlement which they should respect, protect and fulfil.

In the capital city, Lilongwe’s medium-income township of Area 18, as well as in high-earning planned settlements across the country, night guards do not have access to employers’ in-house flush toilets.

For the guards, the only available option is to relieve themesleves along walkways or in plastic bags that are later carelessly thrown away, leading to an increased disease burden and a burden on the already strained national healthcare budget.

Diseases caused by poor sanitation also inhibit the physical and cognitive growth of children and depress their economic potential as adults as much as it reduces productivity.

Studies show that one gram of faeces can contain 10 million viruses, one million bacteria and 1 000 parasitic cysts. These infectious parasites enter the human body through the skin or contaminated food and water, transmitting diseases such as cholera, diarrhoea, dysentery, hepatitis A, typhoid and polio. They are killing more people than measles, malaria and Aids.

A study by World Health Organisation calculates that for every $ 1(K730) invested in sanitation, a return of $ 5.50 (K4 015) is made in lower health costs, more productivity and fewer premature deaths. n